Blackness and Authenticity in Punk

It’s incredibly telling that rock critic and historian Greil Marcus was able to pronounce what punk rock was in 1979 – just two years after Nevermind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols was released, the only album by the band he calls the “formal (though not historical) conclusion” of punk. Punk was a brief flash of brilliance, an explosion whose shrapnel we are still feeling today as the genres that splintered off: post-punk, hardcore, new wave, noise rock, pop-punk, whatever term the editors of No Depression finally settled on, and ultimately all of “alternative” rock. One way or another, punk is the year zero for all rock music that came after; its effects are hard to overstate, and go far beyond the music.

Marcus argues the Sex Pistols took punk’s first-wave to a vitriolic conclusion by redefining it in their image, away from the avant-garde punks of New York. Self-appointed dean of rock critics Robert Chistgau describes the work of “avant-punk” as:

harness[ing] late industrial capitalism in a love-hate relationship whose difficulties are acknowledged, and sometimes disarmed, by means of ironic aesthetic strategies: formal rigidity, role-playing, humor. In fact, ironies will pervade and, in a way, define this project: the lock-step drumming will make liberation compulsive, pain-threshold feedback will stimulate the body while it deadens the ears…

The Pistols dropped the “avant-” and with it the irony and self-conscious artistry of Patti Smith, Tom Verlaine, Lou Reed, and other seminal avant-punks. In its place they put – or at least Rotten and Vicious put – unadulterated, ugly nihilism. This is why Marcus places Sex Pistols at the formal conclusion of punk: they were committed to the destruction of everything, including (paradoxically) rock itself. Unlike the Clash, who were careful to be on the right side politically, the politics of the Pistols was pure negation in its most gleefully manic form. This is what makes listening to Nevermind the Bollocks exhilarating, to this day: the guitars assault the senses while the drums clamor away oppressively, and Rotten – what hasn’t been said about him already? His snarls, his rolled-R’s, half-sung half-growled, that devious cackle; he’s the most convincingly nasty singer rock’s ever seen. When Rotten says he is the Antichrist, you almost believe him.

Rotten’s lyrics are loathing-filled tirades, the product of unfocused dissatisfaction channeled into hate and aimed at anything in sight. Listening to the Pistols is less an experience of having your dissatisfactions reflected back to you than magnified, made metaphysical in scope, and as Christgau writes, aimed at – for the time in rock – those in power. He is a lightning rod for the inchoate rage and dissatisfaction in the listener. He gives the intoxicating feeling of having the freedom to take things too far, of hearing your worst impulses acted out, of glimpsing something beyond the claustrophobia of ordinary life, of, as Elvis Costello sang, biting the hand that feeds you. It can be childish, but also often brilliant and beautiful. The Pistols showed the pure joy of hate.

Still, the Sex Pistols were doomed to fail from the beginning, in both their broader goal of tearing down the institutions they railed against, and in merely surviving as a band. Denial of everything can never make a coherent philosophical position – much less a viable political one. They tried to destroy rock by making it; to deny the past and the future alike while drawing on the former and influencing the latter; to remove themselves from the game of images while astutely managing theirs; to be outcasts signed to a major label. Working under the thought that what we’re offended can show us our true beliefs and expose our hypocrisies, the Pistols railed against the tyranny they saw in English society. But by the same logic they also gave voice to, and thereby legitimized the pointlessly cruel behavior of Sid Vicious. Their contradictions vitalized their music while destroying them as individuals and a band. Marcus is right that the noblest thing Rotten could have done was to leave, to become as anonymous as he could.

Image via

In contrast to the high-minded vitriol (and below-the-belt punches) of the Pistols, there is my favorite of the first-wave English punks, the Buzzcocks. Their EP Spiral Scratch was the first independently released punk album in the UK, beginning the proudly independent trend in punk rock. Rightly grouped among the progenitors of pop-punk, Buzzcocks used the discordance and cacophony of punk on their masterpiece, Singles Going Steady, to give musical expression to the anguish, excitement, humor, and longing of love, infusing the bombast with an ear for pop craftsmanship.

Buzzcocks proved to their peers and the masses alike that the musical language of punk could be used to express something other than hate and boredom; punk, to them, was personal. Their best songs refused to participate in the lyrical refrains of prior punk, from the avant-punk Christgau described to Rotten’s nihilism. “Orgasm Addict,” a charming song about masturbation, would go on to help inspire future generations of self-love themed punk songs (a natural development, perhaps, of punk’s DIY attitude). Pete Shelley sounds exasperated in “What Do I Get” from a lack of love, while on “Everybody’s Happy Nowadays” the band sounds like a cynical reflection of the Beach Boys. They expressed classic punk themes on the bratty “Oh Shit” and “Autonomy.” These were no one chord wonders.

Their most effective statement of purpose is found on the single “Ever Fallen In Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve).” Guitars rip and clash, then momentarily hold back, before repeating the cycle in the neverending game of exhaustion and ecstasy, heartbreak and rapture of doomed love. While the guitars give sonic articulation to the tsunami of emotion which threatens to crush Shelley under its weight, the drums start and stop in turn; rarely has a drum mimicked a nervously flitting heartbeat so well. Shelley’s pointed use of gender neutral pronouns – he was the first openly bisexual musician in English punk – makes the song welcoming of love of all types, a rarity in many punk songs. His boyish yelp is more pained than angry, contrasted all the more by Howard Devoto’s sneering affect on Spiral Scratch. Shelley asks more questions than punk’s usual list of demands, voices a rare vulnerability in a genre seemingly dominated by machismo visions of male invulnerability.

They were decried by many in the punk community as phonies. They weren’t political enough; they were too poppy; they didn’t sound tough. Punk wasn’t always overtly political, of course: the first UK punk single, the Damned’s “New Rose,” was dismissed by Steve Jones of the Sex Pistols as just being about a bird. Nonetheless, in a world where his mere existence as a queer man was made political, Shelley weaponized his vulnerability against the heteronormative culture around him. As he said, expressing a theme Riot Grrrls would later pick up: “Well, I never knew there was a law against sounding vulnerable. And anyway, personal politics are part of the human condition, so what could be more political than human relationships?”

Image via

As for the accusation of appealing to pop: Who cares? Punk isn’t, and never could have been, a total break from the past. The Buzzcocks, though influenced by the Pistols, owe far more to the faux-dumbness of the Ramones, who never had the political pretensions of the English punks nor their unironic straightforwardness. The Ramones flaunted their bubblegum pop influences from the famous first words of their debut: “Hey ho, let’s go!” Their punk wasn’t about denying the past but transforming it: democratizing it to anyone who can manage three cords and reinvigorating it from the bloatedness and naked commercialism of the ‘70s. But where the Ramones interrogation of the past was often ironic, masked by a studied naïvete, Buzzcocks played it straight. They openly revel in Beatlesque melodies, while Shelley admitted to admiring the music of the Supremes and Kinks (a cardinal sin in punk at the time). Punk wasn’t a break with the past or a denial of it; it was a method of interpreting it, a way of making music and of living. They distorted their influences through the lens of punk, and in so doing made pop, but made it more immediate than anyone before them. They may have just been talking about birds (and blokes), but that didn’t make their music any less affecting or radical, nor did it make them inauthentic.

*****

In an analysis of Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain, Chuck Klosterman reflects on the media cycle surrounding the follow-up to the incredibly popular Nevermind. In Utero was purported, prior to release, to be “unlistenable,” and Cobain himself claimed it was going to sell “a quarter as much” as Nevermind. Legendary, and legendarily acerbic, producer and Big Black frontman Steve Albini was producing. Newsweek reported their label, Geffen, wouldn’t release the record as is. To Cobain, though, this was intentional. The album had to be bad – that is, bad in the eyes of the general listening public – to be good in Cobain’s eyes. He was unable to reconcile the sales figures of Nevermind with his own credibility as an artist; the caustic elements of In Utero were atonement for his sins on Nevermind. The feeling Klosterman ascribes to Cobain is guilt: for success, artistic and commercial, for “selling out,” for not being punk enough.

Cobain was struggling with what will be the focus of the remainder of this essay: punk’s fraught notion of authenticity and its implications. Punks rejected the (what they saw as) white middle-class values of respectability and conformity for a “realer,” more “authentic” lifestyle, and to achieve the autonomy they felt had been denied them by those values. Thus, in order to subvert the dominant culture, punk fetishized the ugly over the beautiful, the depressed over the happy, the detestable over the morally sanctioned, and the urban over the suburban. Punks created their counterculture through what Daniel Traber in Cultural Critique terms self-marginalization: they repudiated the privileges afforded them by their race (mostly white), and class (mostly middle-class) and rejected that culture’s values. This reasoning is what led, for example, The Clash to implore “respectable” whites to riot: “Black man got lotta problems/ But they don’t mind throwin’ a brick… While we walk the streets/ Too chicken to even try it.” This rejection of their inherited privileges was in some sense done out of a feeling of moral imperative, which Joel Olston would later elegize in Profane Existence as constituting a rejection of “the white supremacist, patriarchal, capitalist world order.” But it was also a means of acting out the alienation many punks felt and creating a culture for themselves – whoever “them” was defined as.

Differentiating real from fake was crucial to the project of punk. But since punk was defined by the negation of dominant cultural values, the continued hegemony of those values was necessary to sustain its uniqueness and authenticity. Subversion, that is, requires a dominant culture to undermine in order to have meaning. (The power of subversion is therefore limited, as it is defined equally as much by the dominant culture as mainstream forms of expression are – its meaning is always parasitic upon the mainstream.) Thus despite the acute need individual punks felt to distinguish themselves, punk came to be defined by a certain look (think: Richard Hell, lean and hungry, torn clothes manicured to look ragged) and set of behaviors (think: self-destruction). The notion of “authenticity” operating during the first-wave of punk is memorably summarized by one scenester in the L.A. punk documentary The Decline of Western Civilization: "Everyone got called a poseur, but you could tell the difference: Did you live in a rat-hole and dye your hair pink and wreck every towel you owned and live hand-to-mouth on Olde English 800 and potato chips? Or did you live at home and do everything your mom told you and then sneak out?"

Image via

Of course, notions of authenticity varied across and even within scenes; the L.A. punk scene, for example, was criticized as not being political enough by British punks and Greil Marcus, just as the Singles Going Steady era Buzzcocks had been. But the general trends – poverty, rejection of authority, etc. – are enough to see the problematic implications of the notion. Their self-marginalization was based on a constructed vision of the marginalized other inherited from their – typically – white, suburban middle-class upbringing. Thus in attempting to duplicate the experiences and position of the marginalized, they implicitly acknowledged their conception of the other.

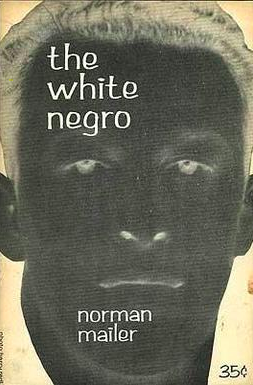

Punk’s articulation of marginalization can be likened to that espoused in Norman Mailer’s essay The White Negro, in which he wrote that free from the restraints of white morality, the black underclass lives a more creative, spontaneous, sexual, and hip life. “The Negro,” Mailer wrote, “kept for his survival the art of the primitive, he lived in the enormous present… relinquishing the pleasures of the mind for the more obligatory pleasures of the body.” In a world marred by the twin horrors of concentration camps and the atom bomb, we [white Americans] must all face the same choice African-Americans did, which is to repress oneself, or to “encourage the psychopath in oneself”: “to explore that domain of experience where security is boredom and therefore sickness, and one exists in the present… the life where a man must go until he is beat… where he must be with it or doomed not to swing.” Punk adopted this dichotomy with a desperate zeal.

The suburbs, seen as the home of the white middle-class, was a slow death-by-boredom, oppression through conformity, and above all, mundane. Only by rejecting that life could authentically be found. (The source of Mailer and punk’s shared notion that the marginalized are more “authentic” can be traced back to a Romantic line of thought where the peasant, “untouched” by civilization, is closer to natural man, and thus more “authentic.” Punk inverted the formula – the urban was romanticized, not the rural, and the life of the underclass was exciting, not simple – but kept the essence the same.)

Image via

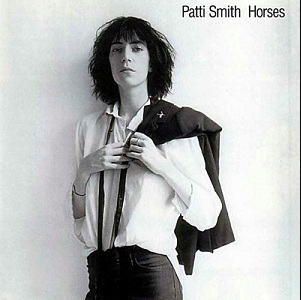

Like Mailer, punk found the authenticity lacking in white culture in Black culture. Patti Smith succinctly restates Mailer’s themes in “Rock N Roll N•••••”: “Jimi Hendrix was a n••••• / Jesus Christ and Grandma, too / Jackson Pollock was a n•••••.” Blackness is identified with coolness and art. Smith also identifies, as a punk, with the Black outsider: “Outside of society, they’re waitin’ for me / Outside of society, that’s where I want to be.”

Through her identification as a punk in the song, Smith recasts her whiteness by aligning herself with a racial other. As Dick Hebdige famously argued, first-wave punk was an attempt to forge a new racial identity, what Stephen Duncombe and Maxwell Tremblay call an “oppositional whiteness” – a whiteness which understands that it cannot be the assumed universal, a raceless race, and which sometimes attempts to stand in solidarity with minorities. Punk’s project of self-marginalization and their creation of this oppositional whiteness was deliberately modeled on their identification with Black culture, particularly the modes of resistance established by reggae. Punks such as Rotten, The Clash, Slits and Ruts worked reggae and its rhetoric directly into their music and fashion, sometimes as literally as The Clash’s cover of “Police and Thieves'' (at punk shows reggae was the only other music allowed to be played between sets). But reggae was more than just musical inspiration: it provided the structure of punk’s rebellion. Its image as “rebel music,” its countercultural hero stars, its lyrical themes and its DIY approach were all directly appropriated by punk. The events of the 1976 Notting Hill Carnival riots in particular, which showed how the cultural expression of reggae could be interwoven with an effective politics, would become an important source of inspiration for punk.

But if in reggae, punk found a language with which to express its outsider status and a model for how to create an oppositional politics through music, fundamental asymmetries remained, and the boundaries between the two were firmly maintained. Punk was, despite its best efforts, rock music, and was therefore given massive exposure by rock critics and scandalized reporting from the newspapers. The biggest first-wave punk acts were also signed to major labels, granting them far greater monetary resources than even the biggest reggae acts had access to. Most importantly, though, punk was, by and large, a white genre, sung in the standard English of England and America; reggae was a Black art form, often sung in Jamaican patois. Both were, of course, deliberately exclusionary, often in similar ways, but the crucial differences between them meant that punk could capture the attention of the powerful in ways reggae never could. The self-marginalization of punks could never eliminate their privileges entirely; a white punk can shave off a mohawk, but a Black reggae listener cannot change their skin color. Punk’s appropriation of reggae tropes and assumption of outsider status can thus begin to look much more sinister.

The scholarship on the punk-reggae connection traces out many important results of the asymmetries spelled out here, but most important here is that punk derived its authenticity by pilfering the form and tropes of reggae. This led to the essentialization of the racial make-up of the two forms, to the subsequent exclusion of reggae artists and those who looked like them in punk. Punk came to think of itself as a white response to reggae, a “White Riot” in The Clash’s famous formulation. This both erased the history of minority punk and proto-punk artists and dissuaded future generations of minorities from participating in post first-wave punk scenes. Their appropriation of outsider status also led to some ugly false equivalences between the oppression faced by punks and minorities, which cross the line from solidarity into talking over and a lack of understanding (as in Smith’s song and The Avengers’ “White N•••••”), and pointing anger at oppression in the wrong direction (as in Minor Threat’s “Guilty of Being White” and the NF-aligned Oi! bands). Their self-marginalization comes to look less like solidarity or a moral stance than poverty tourism, wherein punks sought excitement and an exoticized notion of “authenticity” in the hardships shouldered out of necessity by the oppressed.

The inevitable short-comings of self-marginalization led to punk recreating the blindspots and biases of the dominant culture, to its political detriment. Daniel Traber argues, for example, that punk’s denial of society’s values aimed first at individual autonomy over creating an inclusive counterculture, in effect recreating the individualism of the late-capitalist culture they despised:

The late capitalist alienation these subjects feel is due to their investment in a version of autonomy that perpetuates that sense of isolation by privileging an insular individuation over a collectivity that will allow the inclusion of non-punks.

This precluded larger political change by making the focus iconoclasm, not collective action. Rather than challenging the dominant culture, it merely created an alternative, one which was incapable of threatening its hegemony and in fact relied on that hegemony for its meaning. (And by the ‘80s this was understood – a loss, but a noble one, which is, according to Michael Azzerad, very punk indeed.) The individualist system remained the same because of their focus on atomized autonomy. Richard Rorty sums up the sentiment in assessing Nietzsche’s reverence of Becoming over Being: the inversion was “fruitless – fruitless because it retained the overall form of ontotheological systems, merely changing God’s name to that of the Devil.” Punk, at best, merely flipped the system on its head. At worst, it recreated it in all its ugliness.

*****

Punk authenticity continues to capture our attention, from the torrent of insider histories lionizing punks’ lifestyles to 40 year anniversary reviews proclaiming this album to be the verified real thing. Even those claiming to be above it can’t help themselves from appealing to it, as Pitchfork did in a review of Nick Lowe’s Jesus of Cool when they remark that, rather than scrap it in the “all-too-familiar dialogue of authenticity and reactionism, Lowe cut the crap and made a clever, fierce, and far-reaching record.” And part of the appeal of indie rock (which owes its existence to punk) remains the “authenticity” of its stars, who – unlike all those other, very relevant rock stars – are just like you. Authenticity thus seems impossible to escape, despite the seemingly massive changes that took place in punk since its first wave: the emergence of Riot Grrrl, Queercore and the explosion of zine writing critiquing punk for its racism, sexism and homophobia. They pointed to the flaws in the search for authenticity which they were also liable to, yet again exposing the limits of self-marginalization.

Bikini Kill via

For at the heart of the discussion of authenticity there lies yet another contradiction that punk has wrestled with from its inception. It is exemplified on the one hand by the play of groups like the New York Dolls and the desire for an oppositional whiteness Tremblay and Duncombe identified. It is also reflected in the destruction of meaning intended in the widespread experimentation with Nazi imagery at the time. On the other hand there is the need to “be yourself” by regaining the autonomy denied you by society, to allow for “real” individual expression à la Mailer. Drew Daniels analogizes the latter notion to Russel’s correspondence theory of truth: a performer is being authentic when their private identity matches their performance. But punk has been fighting such straightforward epistemologies from the beginning, playing around the concept of fixed and essential identities. The contradictions of punk’s notion of authenticity carried into the project of self-marginalization, which posits that, to some extent at least, identities are fluid and can be remade at will, but was almost always conceived in terms of finding some hidden authentic self denied actualization by the rigid demands of society.

This is why punks sought to separate themselves from society, and to create new systems of meaning where they could express their true inner selves. This is the great irony and failure of punk – it was only through critical engagement with, not detachment from, their native culture that they could have avoided the failures detailed above. What is needed is a new form of authenticity, one which is not vulnerable to the mistakes of the atomistic individuality and cultural pillaging of punk. What that might look like is the subject for another time, but one can see hints of it in the work of philosophers like Charles Taylor and Michael Sandel, cultural theorists like Daniel Traber, and, I believe, in the music of the Buzzcocks.

In “Oh, What Avails” Alice Munro writes of Joan, a woman who is in the first generation freed from their husbands and able to pursue their desires. “Not self-denial, the exaltation of balked desires, no kind of high-down helplessness. She is not to be so satisfied.” She leaves her husband for a lover, then another, her kids grow up and she stays skinny. But her foundation is slipping, a menace bubbles up which she tries to keep away:

Rubble. You can look down the street, and you can see the shadows, the light, the brick walls, the truck parked under a tree, the dog lying on the sidewalk, the dark summer awning, or the grayed snowdrift – you can see all these things in their temporary separateness, all connected underneath in such a troubling, satisfying, necessary, indescribable way. Or you can see rubble. Passing states, a useless variety of passing states. Rubble.

Joan misses something, however. Rubble is both ruin and promise; all that’s left is to clear it away. If only we could.

Featured image via