The Doom Generation: Fashioning the End of the World

Director Gregg Araki, from the start of his career, never adhered to the norm. His involvement as part of New Queer Cinema in the 1990s defied the mainstream, and his films tell the tales of young, disillusioned queer youth struggling to find their way in a world not meant for them. They’re bold, beautiful, ridiculous, violent, and cynical. And sometimes abducted by aliens.

There’s a rawness and a sensitivity to his films that, though often wild and explicit and not for everyone, reveal a truth that many teens face: no one understands. It’s teen angst capital T, and yet it’s so much more. It’s recklessness and experimentation, a portrait of the alienation and frustration felt by queer youth, especially in the 90s, that only they are forced to bear.

Gregg Araki

“We were very young, dumb, and innocent.The New Queer Cinema was very much a product of its time. It was the height of the AIDS crisis, and as a young queer artist, you were just feeling very energized, like you need to say something. It was the time of ACT UP. There was this need to express what was going on in a way that wasn’t being expressed in the mainstream.”

Araki, with 11 films under his belt, finds most of his cult following through his Teenage Apocalypse trilogy: Totally F***ed Up (1993), The Doom Generation (1995), and Nowhere (1997). His other works, such as Mysterious Skin (2004), a personal favorite of mine, and his recent series Now Apocalypse (2019) are also highly adored. The uncertainty that comes with being a highschooler or twentysomething is ground that Araki likes to touch upon, and the sense of impending doom and apathy that the youth, especially at the time, often faced, breeds stories that deserve to be told.

“When you’re in your 20s or a teenager or whatever,” says Araki in his interview with The Ringer, “you’re so unformed. You don’t know what you’re gonna be or what’s gonna happen. There’s such an uncertainty there and so much confusion and you’re really just trying to figure your sh** out. For me, that’s always been such fertile ground creatively and dramatically.”

Araki’s films stand out, in particular, due to their visuals. The fashion is bold. The kids are beautiful. The backdrop of a nearly apocalyptic Los Angeles combined with characters that are just looking to find their way anywhere and nowhere heightens their imminent downfall. His characters, fashionable as they may be, use style as a way to rebel against a world looking down on them.

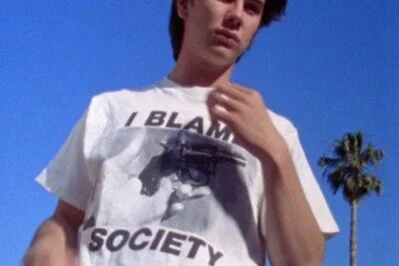

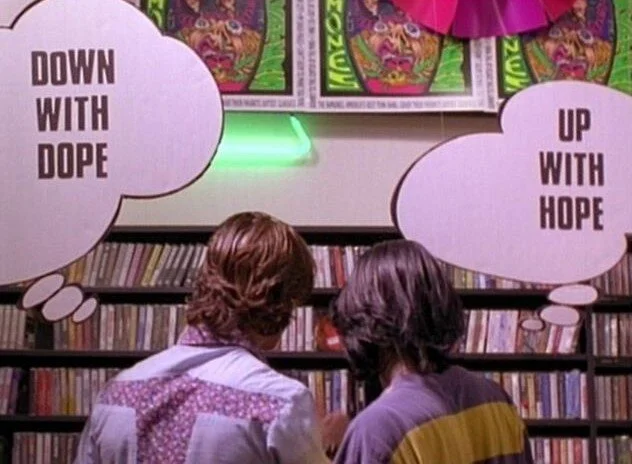

Sometimes, that cynicism is obvious. One of the most viral screenshots of Araki’s movies is James Duval donning a shirt that blatantly states, I BLAME SOCIETY. In The Doom Generation, Johnathon Schaech’s character Xavier Red is often seen in a black D.A.R.E t-shirt—a direct mockery of society itself at the time. Two girls of Nowhere walk around with matching clear tops—one says WHAT, the other says EVER. It’s almost laughable how prevalent their displeasure is, but it’s obvious because it simply can be. The messages that the kids in Araki’s universe are receiving is that being angry at the world is a normal thing, that vulnerability is out and apathy is in.

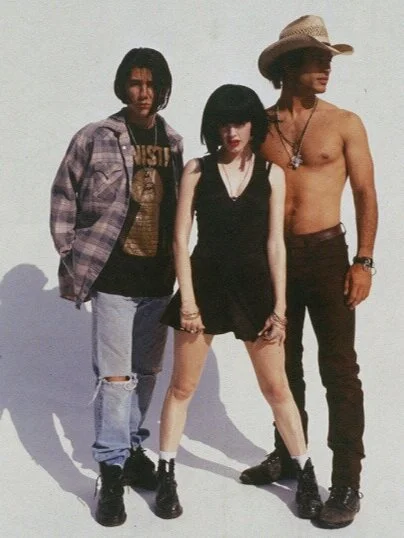

The Doom Generation (1995), second in the trilogy, showcases this apathy tenfold. The film follows Amy Blue (Rose McGowan) and Jordan White (James Duval), two teenage love birds that pick up drifter Xavier Red (Johnathon Schaech) on a trip to nowhere. All the while, as they make their way through an apocalyptic America, Amy’s previous “lovers” are out to get them.

Amy Blue is the epitome of indifference and anger, and it shows not only in her dry one-liners, but her style as well. She’s often seen with a pair of big, dark shades on to hide her eyes. Her chunky silver rings, skull lighter, blunt black bob, blood-red lip, over-sized leather jacket, and huge combat boots show that she’s not to be messed with. If her aloof and often callous personality isn’t enough, then the word KILL written across her knuckles should do the trick.

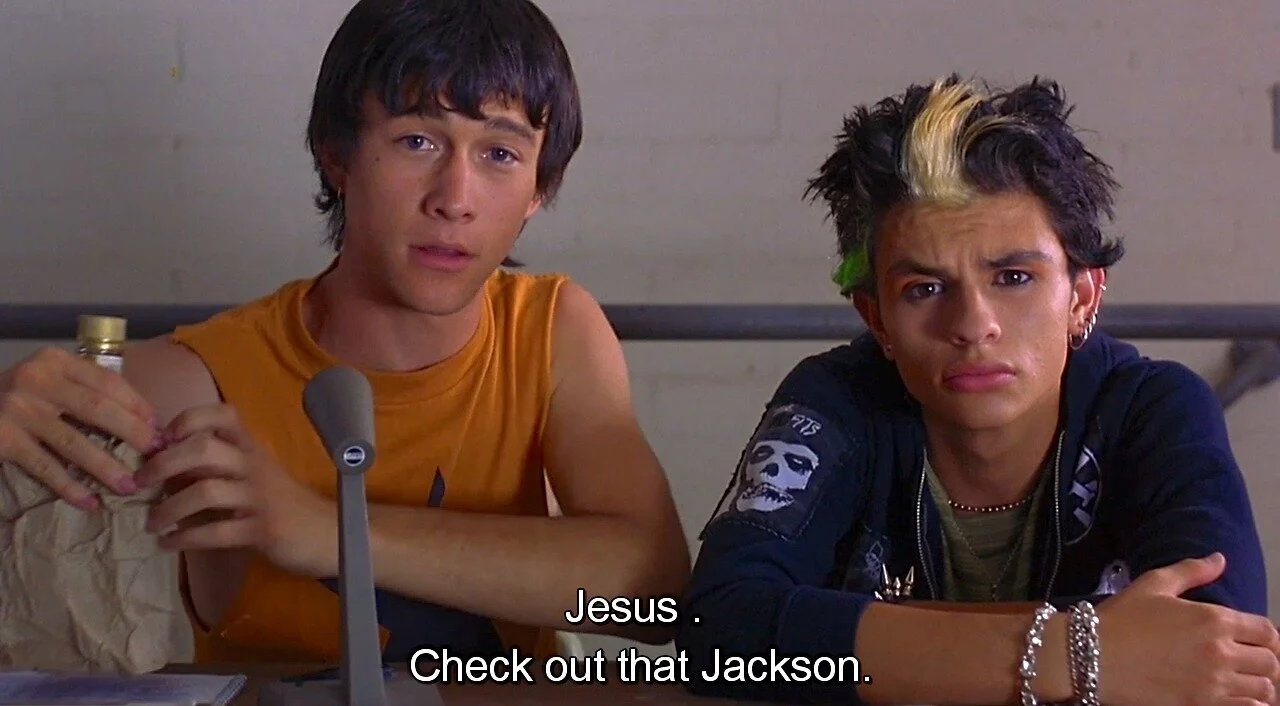

It’s quite the contrast from her boyfriend Jordan White. His personality, sweet and dopey, doesn’t seem like it would mesh with Amy’s at all. But, in fact, it does. They share the same anger at the world, the same desire to leave and never look back. He fits by her side perfectly well—visually, too, in his ripped jeans and baggy flannels. With the addition of an eerily charming and reckless (and, often shirtless) Xavier Red, they seem to make the perfect, fearless trio. If you’ve seen the film, you know that’s debatable.

As the trio pass through mini-marts, drive-thrus, and motels on their journey through Nowhere-America, they’re stalked by a (very obvious) sense of impending doom. Their totals come out to $6.66. Billboards and signs in the stores read Shoplifters Will Be Executed and Prepare For The Apocalypse.

In a world like this, how could they care about anything?

The youth of the finale of the Teenage Apocalypse trilogy, Nowhere (1997), are nearly futuristic. The film follows a day in the life of teens in Los Angeles merely attempting to survive the strange and out of the ordinary. That sense of impending doom is still there in odd ways.

Araki’s it-boy James Duval makes another appearance here as Dark Smith, who often dreams of the end of the world. Over the course of the day he gets warnings of the Armageddon, witnesses an alien vaporize three girls with its ray-gun, and watches his friends self-destruct in the process.

Their blunt-cut hair, colorful garb, and funky sunglasses, combined with the vivid saturation of the film itself, amplifies the fact that everything is not what it seems. They utilize bright colors to not blend into a dying world, and stand out to keep themselves afloat.

Sometimes, Araki gives us the opposite, using style as a way to create a caricature out of those who “fit in.” The three valley girls in Nowhere have no sort of identity or autonomy separate from each other, save for the different colors of their clothes. They have no names, simply casted as Val-Chick 1 (Traci Lords), Val-Chick 2 (Shannen Doherty), and Val-Chick 3 (Rose McGowan). Their hair is teased high. They wear their sunglasses on their heads, not on their eyes.

Years later, in Mysterious Skin (2004), Jeffrey Licon’s character Eric looks as if he was plucked out of the Teenage Apocalypse trilogy and dropped into the early 2000s. His dyed hair, dark liner, black lipstick, and silver hoop earrings allow him to stand out amongst the rest of the characters.

Much like us, these kids walk around confiding in their friends with foreboding thoughts. I feel really weird tonight, like something’s gonna happen, Jordan White admits to Amy Blue. I just wish things weren’t so messed up and confused is all, Dark Smith laments. With feelings of anxiety and dread peaking in young people today, stories of struggling teens are relevant now more than ever. Without the aliens, that is.

Featured image via