Remembrance Reenacted

Meta-level questioning within a text is not unique to postmodern writing, but it is often uniquely boring in it. There is something simultaneously unconfident and self-indulgent in this tendency at its worst, which reduces fiction to meta-fiction and theory to meta-theory (a sure sign of crisis in any field). And when combined with the pervasive practice of critique it takes on a fearful air, as if the critic must beat others to the punch in pointing out her own maneuvers and complicities, in spotting the places her text, too, slips out from under her. She must show that she is not immune to her own suspicious gaze, but, like Moses Herzog, is impotently self-reflexive.

Yet in art depicting trauma these questions are unavoidable: can art accurately represent trauma? is it irresponsible, or worse, exploitative, to use trauma for art? Will one’s audience react appropriately? William H. Gass, never boring, opens with these concerns in his fittingly mammoth novel The Tunnel, the private reflections of historian failing to write the introduction to his opus, Guilt and Innocence in Hitler’s Germany:

I’m afraid that willy-nilly I’ve contrived for history a book’s sewn spine, a book’s soft closure, its comfortable oblong hand weight, when it ought to be heavier than Hercules could heft. History is relentless, but now it has a volume’s uninsistent kind of time. And hasn’t the guilt and innocence I speak of there become a simple succession of paper pages?

Panh’s clay figures (image via)

Art is, first, materially inadequate in the face of trauma. Rithy Panh, in his film on his childhood under the brutal Khmer Rouge in the 1970s, The Missing Picture, leaves one feeling as inanimate as one of his clay figurines when he says, “It’s not a picture of loved ones I seek. I want to touch them.” His film cannot bring back the dead, undo his suffering, or remake the past.

And film can misrepresent the past, enchanting its viewers while doing so. Panh, who had found comfort in his neighbor’s movie collection, recalls wishing that a plane flying overhead would drop a camera for him. Then, surely, someone could document their suffering. Then, surely, someone would know, someone would care. Instead the only images the cameras captured were propaganda films. In one a group of children in perfectly ordered, patriotic lines work in a field; but look closely: “one sees the fatigue, the falls, the gaunt faces…” But one doesn’t look closely. One sees what was meant to be seen. (What do we see in videos of police brutality? Right-wing media undermine the character of Black men and women killed so we see a criminal – not a person, despite all appearances – being killed.) Panh fills in the missing pictures by interspersing and overlaying clay figurines on the propaganda footage, the only images he has. They resemble the toys of a childhood lost, their vague expressions as unchanging as the monotone of his narration.

The viewers of The Missing Picture cannot feel the desperate agony of their hunger, their inexhaustible exhaustion, the bodily fear of government work inspections, the sickening sight of corpses. “Nothing is so soon forgot as pain,” Adam Smith wrote in The Theory of Moral Sentiments. One cannot sympathize – by which he means something more like empathy than our idea of sympathy– with the pain of Hippolytus or Philoctetes on the stage, because one has forgotten the feeling of pain. Panh can only substitute images for pain. He shows a picture of three young children: healthy, average. They died of starvation in a work camp. Pictures, like clay, don’t suffer.

Image via

Panh and Gass are concerned as much with the motives of the artist as with the limits of the medium itself. The movie no more brings back his family than the clay is alive; the clay becomes emblematic of the inertness of film. Their flesh is cold, they do not respond to his touch – but they are all he has. Joshua Oppenheimer, in his now-classic The Act of Killing, seeks to provide a defense of film through the (some say dubious) conversion of mass murderer Anwar Congo. The film follows a group of aging gangsters and paramilitary leaders – many now members of the government in Indonesia – who participated in “anti-Communist” purges of 1965-66. They write, direct, and act in a movie depicting their exploits. The government hopes for a propaganda film, while the lower-level killers we follow variously want to assuage their consciences, misdirect history, and star in an action-comedy.

As his artistic ambitions grow, Congo reflects on how propaganda films and imported American gangster movies influenced him. In the former he found justification for brutally murdering hundreds (he was “proud because I killed the Communists this film made to look so cruel”), in the latter a demeanor to imitate (he was called a “cinema thug” for stalking around the movie theater). Recollections of Elvis and Scarface interpolate memories of killing, as if both were equally banal parts of a rebellious youth. Congo sophmorically works these influences into the film – even Elvis’ movies were better – while attempting to rewrite it as self-justification, or perhaps merely self-exculpation. “Imagine if the film suddenly ended with this scene” of him being decapitated, Congo asks. “People will think this is my bad karma. But if this is the beginning, then all the sadistic things I do next will be justified by the sadism here.”

Congo proudly displaying his killing method (image via)

But Congo, through acting in a scene where he is strangled in the same way as many of his victims, is able to sympathize with them (or so he thinks; one of the filmmakers points out that, unlike his victims, he knew he wouldn’t die (film does have its limits, after all)). His attempts at rationalization and self-mythologization fail, and Congo finally faces the extent of his guilt. Susan Sontag wrote that viewing images of atrocity desensitized one to them; maybe she should’ve looked into acting. In the film’s final scene, Congo returns to the site of many of his murders, threatened with vomit as he looks around the scene. “I did this to so many people, Josh. Is it all coming back to me? I really hope it won’t. I don’t want it to, Josh.”

For Oppenheimer, Congo’s conversion, if it doesn’t absolve film, does at least downgrade the indictment. It also answers the meta question about depicting trauma. Where the clay reenactments of Panh served as implicit critiques of the medium, the reenactments of The Act of Killing succeed in converting one of the killers. The comment of the filmmaker somewhat undermines this story, however: Congo didn’t feel what his victims felt, so his sympathy was imperfect. Smith and Oppenheimer, it seems, sought sympathy from art depicting pain and predictably failed to find it. Does that mean that art cannot – should not – represent suffering, given this inexorable failure?

To answer this question we must answer another: What do we want from art depicting suffering? Empathy? – for whom? from whom? Demanding empathy can quickly slide into the expectation that marginalized artists produce empathy in their non-marginalized audience, who must be convinced to care (imperfectly, as Smith and Oppenheimer found). Beauty? – how, out of so much suffering? how, without reducing it to mere words, or paint, or film? Expression? – but this avoids the question of audience.

Who the audience is, and what purpose the depiction of suffering is meant to serve, centers the concerns over “trauma porn,” art in which the suffering of some, usually a minority group, is used to service the guilt of others, usually a non-minority group. In movies like The Blindside and The Help the pain of the Black characters is little more than an impetus for the White characters’ growth – and the emotional release of the White audience. As with any other label, however, trauma porn can be used as a tool of evasion, a way to safely ignore the suffering of others.

Panh does not seek empathy, and his clay figures are hardly beautiful. The Missing Picture is an exercise in expression, but he never forgets the audience – the film is not made, or not solely made, for himself. What Panh seeks is remembrance, personal and public.

****

Image via

Why remember? As philosopher Charles Griswold argues in his book Forgiveness, Nietzsche held forgiving, which requires memories of wrongs inflicted, in contempt as a sign of weak ressentiment. Forgetting is nobler. Ancient perfectionist theories were even less forgiving: for Plato, the moral individual cannot be harmed by another, so has no reason to forgive. They have no reason to remember.

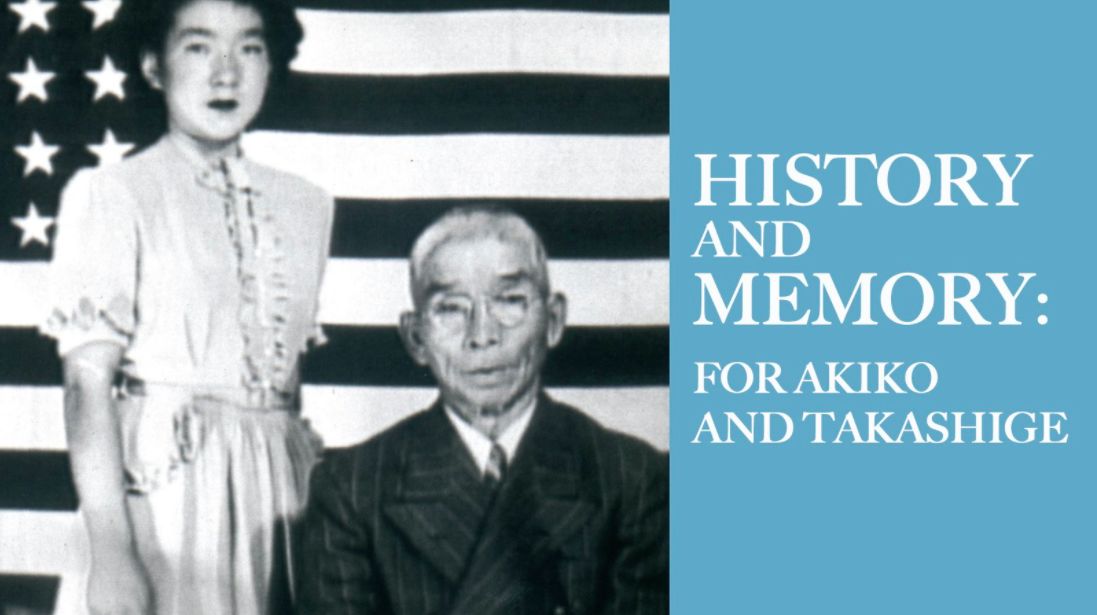

The remembrances of Panh and Congo and his fellow murderers are public as well as private; in other words, their films are expressions of historical consciousness. To this list we can add Rea Tajiri’s 1991 short film History and Memory: For Akiko and Takashige. Tajiri travels to the site of her mother’s internment in Arizona, to reconstruct what little she has been told. The elder Tajiri “forgets to remember,” as she modestly puts it – but she remembers why she must forget.

Image via

The subtitle makes clear the private aim of the movie, but it is also for us, America. The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 formally apologized for internment of Japanese Americans during the War, and instituted a fund for public education (a small plaque and bell lamely commemorate the site of the camp). Despite these measures, internment and her mother’s forgotten memories register mostly as felt absences, which Tajiri struggles to represent on film. For instance, while her father fought in the war and her mother was “relocated” their family home was condemned and torn down. The empty lot where it once stood is juxtaposed with text describing the view from 100 feet above it – both unseen presences, described but not shown. The film takes on the qualities of the half-forgotten memories of internment, her mother’s and America’s, threatened with incoherence and splintering. As film scholar Janet Walker wrote of The Thin Blue Line, the film itself is traumatized.

The story of the repression of internment is yet another specter haunting History and Memory. “What would it mean,” asks memory studies scholar Marita Sturken, “for Americans to remember the names Manzaner, Poston, Tule Lake, Topaz, Minidoka, Heart Mountain, Jerome, Gila River, Amache, and Rohwer in the way they know the names Auschwitz, Dachau, and Buchenwald?” I knew none of those names. (The Equal Justice Initiative has likewise been placing historical markers at sites of lynchings and other racial violence, both to document them and to amend the self-congratulatory historical markers littering America’s roads.) The struggle to re-remember is a struggle for justice. Tajiri remembers so we do, so her mother doesn’t have to.

Image via

Panh remembers to forget, to exorcise the trauma; yet remembers compulsively, in the way trauma victims often do. “I wish to get rid of this picture of starvation and death: so I show it to you,” he narrates, all the more tragically for his plainspokenness. The weight of memory might be shared by telling us, and forgetting begin.

The Act of Killing, in addition to being film’s mea culpa, is an exploration of how one’s answer to Why remember? influences how one remembers. Congo attempts to remember to absolve himself, but cannot escape his guilt. (Which does not stop him from trying: he even tries adding a scene in which, incredibly, a man thanks Congo for killing him and sending him to heaven.) The government supports the film for a particular account of the massacres to be remembered, one where the Pancasila Youth, the leading paramilitary group, is ferocious while somehow slaughters the “Communists” “humanely.” Adi Zulkadry, an associate of Congo, appears to recognize the truth of what they did – he constantly corrects Congo’s attempted rationalizations – but, with a remarkable awareness of his own moral psychology, seeks to save their image in history: “It’s not a problem for us. It’s a problem for history. The whole story will be reversed… if we succeed with this scene!” Herman Koto, Congo’s incompetent sidekick – he cannot even manage to bribe his way into office – wants to tell the truth just because he thinks it makes him look cool. Another killer wants not to remember at all: “War crimes are defined by the winners. I’m a winner. So I can make my own definitions.” And history is the story of war and murder, anyway, so why remember his?

Their arguments about plot and sequencing are thus proxies for how they will be remembered, and why they should remember at all. The others object to Congo beginning the movie with his death, making the murders a revenge plot; “This is history!” Zulkadry shouts. But he too tries to alter the story to accommodate an impossible position. “There’s been no official apology – but what’s so hard about apologizing?” he asks. He lives with a double historical consciousness, denying his own guilt on the one hand and demanding the government admit it on the other. If the massacres were wrong, what justifies his part in them? He cannot consider this question, if he is to save himself the guilt.

At the edge of the film sits a related question: Who remembers? They hire an actor to play one of their victims, who tells of how his stepfather, with whom he had lived since birth, was murdered by the Pancasila Youth and left splayed under an oil drum. He likely saved his family by going outside to intercept them, but his heroism is not remembered as such. The man tells this story with a smile to his stepfather’s persecutors – he must tell it as a joke, for the death of a subversive is no tragedy. Like Panh he must tell it, however he can, so he must remember incorrectly, because if a Communist died a hero, what does that make his killers? And if his son grieves his death, what does that make his son? In the film he is gagged and strangled, his story mis-told, the unintended symbolism lost on the killers. He can’t remember properly – not until they do.

Cover image via