Fernweh~6: Turkey

fernweh

/ˈfɛʁnveː/

farsickness or longing for far-off places

So far, the fernweh series has focused on the far-off places that I have been longing for and have never been to. In these times where we have limited access to travel, the series was an involuntary attempt to answer the question “which one broadens your perspective more: reading or traveling?” As I only had the option of reading, reading it was. Yet, now, a first-year who’s been to the campus for the first time, my longing for the far-off places expanded to my country of departure. Farsickness intertwined with homesickness in a foreign place where I should supposedly call home. And my once so familiar home is a distant place that I now miss. As dramatic as it sounds, I wanted to be a foreigner. Now, I am. And, no, it is not what I was hoping. It is just me, glancing, with a rusty sense of settlement.

I have quickly discovered that I am not the only one with a faraway home, with a need to get used to this ~situation~, with a sense of disconnectedness (from home or from where we are now as a society). That’s why I decided to change the series's structure into a journal format, where I will be interviewing people who identify themselves as those belonging somewhere else. I hope Fernweh can become a voice to the quotidian narrations of the people we see on campus every day.

Today’s Fernweh visit will be to Turkey, where I miss the most right now...

Su: What does it mean to you when I say “Turkish Clothing”?

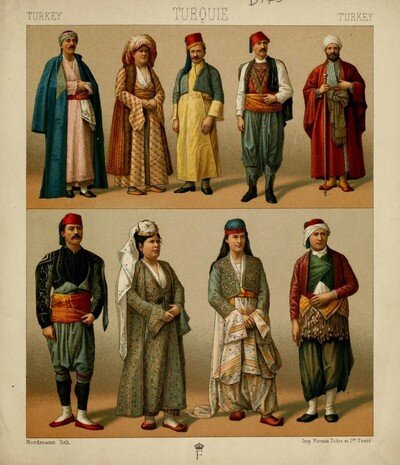

Anonymous Student: I believe, not so weirdly, that it reminds me of the traditional Turkish clothing that we currently wear only on special occasions. However, I won’t be able to give you a very specific example as there are probably more than hundreds of traditional clothing spread across Turkey. As you may know, there is a great ethnic and geographic diversity in Turkey. There are not only traces of early Asian civilizations but also of Mesopotamian and European civilizations. Also, the geographic position of Turkey was on the path of multiple migrations and trade roads. So, I believe that is reflected in the great cultural variation in the current borders. When you say Turkish clothing, that is why I don’t think of modern, monic clothes but more of the traditional and diversified clothes.

S: How would you describe the traditional clothing in Turkey, then?

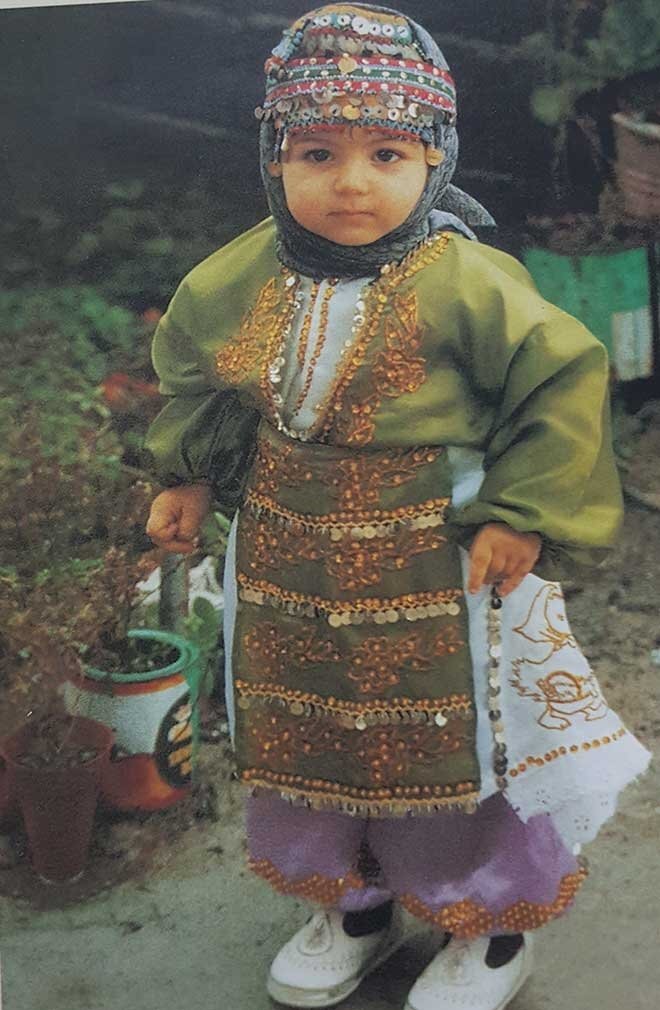

AS: My previous answer is also applicable to this question. However, I can talk about the modern-day integrations of traditional clothing. Today, there are not many people who wear traditional clothing for everyday purposes. They are usually worn in folk events, such as dance and music competitions. Like in East Asia, it is not common to wear those clothes on national holidays. However, that is probably due to most of the “Turkish” traditional clothes being either a form of old, local military costumes or having a connection to those times. The “historical” clothes that the wealthy or the nobleman wore are not considered “traditional clothes” to my knowledge. For example, instead of the padishah and harem garments that are highly represented in the media, the clothes that we, as the folk, consider traditional are simpler and have the marks of the local geography. On the Aegean side, there are Efes who wear more Mediterranean-motivated clothes. On the other hand, in central Anatolia, you can see the historical marks of the Turkic tribes.

S: Actually, it is definitely not surprising to come across this differentiation between folk and noble clothing, considering my old entries. It has also become something typical to see the traces of national history in the evolution of fashion. How would you reflect on this?

AS: I definitely agree with that. Turkey's geography has gone through very distinct historical periods, ranging from nomadic life to the Ottoman empire. Also, in between these periods, there were time intervals where the influences of people shifted from Asia to Europe on a constant loop. There were times marked by what Turkish people call “modernization,” “westernization,” “East influence,” etc. Besides, even though Turkey is considered mostly an Islamic country, it was not like this for a long time. Even when you label the “Islamic” times as a period of historical focus, there was, and still is, a great majority of other religions and cultures present in Turkey. That is why our geography is considered multicultural. With each pivotal change in history, the region gained one additional dimension to its culture.

S: How would you describe today’s clothing?

AS: It is...pretty average *laughs*. On the street, you will mostly see casual or business clothing that you can find pretty much everywhere on Earth. However, I noticed here in the US that there is this preconception of Turkish people wearing hijabs, fezzes, and shalwars. I can understand the hijab and shalwar misconception to an extent as the hijab is worn as a personal choice by women who believe in Islam, and the shalwar has its modern rearrangement as sportswear, but the fez? It is a garment that left when the Ottoman Empire fell. And I don’t know if I should feel this way, but when somebody comes to me and asks me why I don’t wear a hijab or veil, I feel weird. It is a personal choice at the end of the day.

In terms of the fashion industry, I am not that knowledgeable. However, today, there is this new movement focused on embracing traditional Turkish motifs. I also see this in art. It is always pleasant to see such aesthetic combinations.

Thumbnail image via