Cruella's Devilishly Remarkable Costume Design

Disney live-action remakes of animation films have come under the scrutiny of a vocal number of fans of the originals. Either from their uncreative approach at almost precisely copying the source material while adding nothing more than a little sprinkle of overcooked CGI and a pinch of Uncanny Valley to many more abstract or object-based characters like the Genie from Aladdin and Lumiere and Cogsworth from Beauty and the Beast, or from the movie’s blind faith towards recreating the magic of the animation instead of what makes the original films great, these motion pictures have received a lot of hate regardless.

This criticism is not particularly part of my experience. (I appreciate a lot of aspects of 2019’s Aladdin, including the Bollywood-inspired dance sequences and Jasmine’s new song and her portrayal as a princess who cares about politics, Agrabah, and its citizens, earning the position of Sultana, and 2019’s Lion King is a visual and technological marvel regardless of the “emotionless” character facial expressions.) Moreover, even if such opinions thrive in places like Metacritic, Twitter, and sometimes YouTube, box office numbers provide a whole new worldview to the vocally unbeloved motion pictures. As two examples, Beauty and the Beast made $1.26 billion globally, while The Lion King made $1.56 billion worldwide.

Image Via

This more optimistic perspective to the live-action remakes where, in the majority of times, people keep on coming back for more, not unlike the MCU movies with the amount of money both franchises make with their hits and misses, partially proves that not everybody who watches a movie and enjoys it goes on social media to defend it, so the unilateral view presented about them on social media is not the only reality of the situation (even film reviewers have disparate opinions). That is a factor, amongst many others, people should consider when reviewing a movie’s performance above only believing in the words of the vocal majority. If someone does not like how Disney treats their live-action remakes and finds a community of people who agree, they can and should have their opinions, and Disney can learn from some critiques, but to believe that their views are the truth of the matter and that everyone else stands with them is misguided. Still, if you have either liked or disliked the movies, you are very much entitled to do so.

Controversy (and a touch of audience alienation) aside, the most recent episode of this “love it or hate it” franchise, rather a quasi-installment to the list of Disney live-action remakes, is Cruella. Actually, in my opinion, my little rant above was totally unnecessary for this post because simply put, Cruella falls considerably far away from the wardrobe of remakes, both in content and tone, so I may have just borrowed your time a tiny bit more than I should have. Oopsie. Either way, this The Devil Wears Prada-esque feature-length is more akin to a prequel than a remake (especially if you consider the 1996’s 101 Dalmation to be one of the first Disney live-action spins and that Emma Stone’s character is a past version of Glenn Close’s) and more closely resembles Maleficent in its focus on making a villain the protagonist.

Image Via

The only manner in which Cruella could be called a pure live-action remake would be if, for example, 2019’s The Lion King was about how Mufasa and Scar’s father was a segregationist and dictatorial king against the Hienas, and Mufasa was congruent to such policies while Scar was a rebellious opponent of the marginalization of the species. Or maybe if 2015’s Cinderella featured an intricate Regency or Victorian-era love triangle between Lady Tremaine and Cinderella’s Mother and Father and how Tremaine poisoned Mother because the antagonist got impregnated by a husband she did not want to have due to an arranged marriage (Father was going to be her original match) and began to be increasingly afraid that the horrible husband would send Drizella and Anastasia away due to certain congenital conditions that made them look different. Hence, the only way for her to conquer Father back was to poison her miserable husband, inherit his fortune, and then kill Mother to get her out of the picture. But none of the situations described above are true, and I am rather having fun stalling the audience from the post’s actual content. Yet, it appears that with Cruella, a movie that is being compared with DC’s Joker in its depiction of a protagonist’s downfall into badness/madness, her appeal comes from seeing what made Estella become Cruella, a wholly original interpretation of such a character. Are we supposed to morally like the villains they come to become? Of course not, but at least Disney is adding a little more PG-13 spice into what makes their iconic villains both likable and “bad” with this film, which does precisely that with literal style.

Cruella seems to have appeased some critics that are calling it “the best live-action Disney update yet,” update being the keyword here since “remake” entails the unquantified modification of a plot in structure, characterization, context, and production, while “update” has a more varied tone to the number of narratives one can tell inside an already existing story (the end of the movie creates a direct reference to the original). Nonetheless, for those who still believe Cruella is a remake, the fact that it exists as very much its own thing years apart from the story in 101 Dalmations without many special effects has offset most, if not all, the criticism the remake-haters have about this Disney franchise. If somebody is to criticize the movie, they will now focus on its inherited flaws (if or when they find it) rather than the fact that it is trying too hard and failing at reproducing the magic of the original. Now, I have my own opinions about Cruella, but I will keep them separate so I can divert my attention to breaking down the undeniably gorgeous and highly stylish costume designing of the movie, one of its undoubtful highlights. This may sound inconsiderate and rude, but if a person left the film thinking that its costume designs are “average” compared to other movies in general, I am astounded at that person’s blind moxie.

The Undertaking

Image Via

Two-time Oscar-winner costume designer Jenny Beavan is a master in her craft, and Cruella solidified her status as such even more. Previously working on Mad Max: Furry Road, The King’s Speech, A Room with a View, and on both installments of Robert Downey Jr. and Jude Law’s Sherlock Holmes series, Beavan was contacted by Disney producer Kristin Burr to helm the project after helping her with 2018’s Christopher Robin, a movie that is in itself a unique spin on Winnie-the-Pooh. In an interview with Popsugar, Beavan mentions that after reading the script for the first time, the designer was doubtful is she would be able to take the movie on and that she started “everything — with complete terror, obviously, because it was so enormous.” Enormous such a creative undertaking was.

The main character and the antagonist had 80 costumes weaved for them combined: 47 for Estella/Cruella, played by Emma Stone, and 33 for the Baroness, played by Emma Thompson. For the rest of the principal cast, 197 garments were constructed. Even if these numbers don’t feel very magnificent, especially when you compare Daphne’s 104 dresses alone in Bridgerton (granted, it is a Netflix series with eight episodes in its first season), making almost 80 Haute-couture garments that are supposed to depict different levels of creative fashion designing, with varied shapes, colors, fabrics, cuts, and sewing skills, be unique in their own ways is sincerely astounding. The amount of variation found in the sketches sprinkled throughout Cruella alone is enough for a whole fashion show. But then, every time the Baroness appeared in it, she wore something different, highly fashionable, and sometimes even timeless, a result of her being, first, an aristocrat, and second, the head of her fashion label. To design 33 unique premium-looking garbs for one movie is to create and weave for a small portion of the celebrities from the Met Gala or an award show at once, and that is impressive. But then, the movie depicts around six major fashion events, and they all feature Haute-couture for both Cruella and the gala guests, perplexing me even more about how a group of fashionistas and seamstresses were able to come up with all the costumes for it.

Image Via

Image Via

I am going to skip over Estella’s garments (more subtle than her counterpart’s but still complex and fashion-forward) to highlight only Cruella’s and the Baroness’ in the following paragraphs, but I need first to stop and say that the work Jenny Beavan and her team put into crafting all of Cruella’s looks alone should be recorded in film history, preferably in a museum displaying all the original costumes. Now that I said it, let's talk about inspirations.

Rock & Vogue

Cruella’s story transpires in the British ‘70s, a time of rebellious countercultural movements marked by underground musical genres like hardcore and punk rock (Sex Pistols and The Clash come to mind) and alternative designers such as Dame Vivienne Westwood, who brought modern punk and new wave fashion into the spotlight. In an interview with Vogue UK, Beavan explains that the designer was one of the inspirations for the rebellious personality Cruella imbues into her work, together with BodyMap, an early 80s fashion label marked by their peculiar fashion shows and clothing with lots of prints and layered shapes, and Nina Hagen, an internationally renowned German punk and new wave singer known for her subversive sense of style (a combo between Madonna, Kiss, and David Bowie). In a virtual press conference for the movie, she further mentions Galliano and Alexander McQueen as part of her “mood board” inspirations, and the latter’s aesthetic, which Cruella’s director Craig Gillespie praised while talking to the LA Times for the “shock value of his shows and the creative outrageousness of some of his work,” heavily influenced how Cruella was visually portrayed and the way she planned her pop-up shows, even if McQueen found his label in 1992.

Moreover, the ‘70s were a time when what was in vogue expanded the expressive freedom of ‘60’s clothing, now featuring nipped, tight waists, exaggerated flared shapes, and more. Talking to Collider, Beavan spotlights Dior, Balenciaga, and other great ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s fashion designers (like Elsa Schiaparelli) as primary inspirations for the Baroness’ evolving aesthetic, after she “looked at the really high fashion of the period, particularly [on] Vogue,” a resource that is “very available online.” In the movie, the Baroness appears as a character with a style that I would call chrono-fluid, meaning that her sense of fashion does not belong to only one decade but rather exists in a fluid state between years. For instance, her closet pulls from the ‘50s and ‘60s aesthetics while staying fashionable 5 or 15 years later. Basically, throughout the movie, the Baroness wears both past and present designs from her label, and as mentioned before, Beavan looked into previous years to build the antagonist’s look, and because she has been in the fashion business for a long time, the character’s sense of style both exists inside and transcends the borders of time.

The ‘70s were the stylistic soul of Cruella’s fashion, primarily due to the visual aesthetic of the time as explored above, but Beavan also imbued the decade into the process of preliminary dressing and fitting of Cruella’s movie costumes. In the Vogue UK interview, writer Radhika Seth asked her if her team had sourced vintage clothes from London and New York. The costume designer explained that, like she used to do in her past — getting her clothes on vintage shops, especially on Portobello Road because she could not afford more popular brands like Westwood or Biba — Beavan and her team found different garments from London’s Portobello Road Market and A Current Affair fair on Brooklyn, New York City, to build the preliminary fitting outfits for Emma Stone by combining different garbs in a myriad of combinations until they felt suitable for her and the portrayal of Estella and Cruella. One of Braven’s main goals was to not overdue the already excessive ‘70s style because then the movie’s clothing could look more like a party costume than actual garments. Moreover, she did not intend to be entirely faithful to the ‘70s, so Cruella could still feel like a contemporary piece based on the past. In the end, even though none of the garments in the film were part of this vintage mish-mash of elements, rather being remade following the overall shape and image created by the preliminary costumes, the whole idea of taking vintage clothing and reshaping them reverberated into the narrative in Estella’s approach to creating Cruella’s outfits, especially Baroness’ red dress she wears for the Black and White Gala.

Cruella- Red Ravage

Image Via

Image Via

Now that the inspirations segment is done, onto the designs themselves. Approaching Cruella’s overall palette, Jenny Beavan mentions that the eponymous protagonist’s colors “were clear: black and white with some grey, plus the red for the signature moments” (and her lipstick). Such a scarlet moment arrives in the Baroness’ above-mentioned Black and White Gala, where the character of Cruella first steals both the movie and the fashion scene. Draped in a white silk robe (maybe charmeuse) with a black eye masquerade mask and her iconic black and white hair, Cruella makes her first fashion statement by setting it on fire (all special effects) to uncover her interpretation of the Baroness label vintage red dress in an event where people cannot wear color.

In the Collider interview, Beavan explains that she found a cheap red dress in a shop in Beverly Hills, and upon seeing it on Emma Stone’s body, she thought, “This could almost work, she looks so good.” However, because the fashion moments were dictated by the script, it already mentioned that the Baroness’s luxury fashion label once sold such a dress, so it could not look like an inexpensive gown. Thus, taking inspiration from Charles James 1955 Tree dress, an iconic 20th-century designer known for his fascination with exploring and conforming to body shapes and a highly structured aesthetic, the costume designer and her team decided to remake the gown they purchased before to match the story, where Estella would have deconstructed and reconstructed it with her imbued rebellious persona. In Beavan’s words, “The idea was that there was enough fabric in this dress, (...) that you could just about believe that she made it from this original work that she found.” The idea came from fashion artisan Ian Wallace, who also finalized its look.

Cruella-Unruly Highlights

Image Via

Image Via

Image Via

Image Via

Image Via

Image Via

Throughout the film, Cruella also appears briefly with highly creative and majorly fashionable gowns in what Beavan calls photobomb moments since they feature the protagonist stealing the entrance buzz from the Baroness in front of a big fashion event. For a fan of fashion, these consecutive scenes that display Cruella in her high-collar leather biker jacket, orange sequin pants, and black makeup spelling “The Future;” in her British General uniform-inspired blue and red coat with adorned epaulets with golden miniature horses and carriages, black and white crown, and large frilly pink and black train skirt; and in her newspaper bodice and garbage-patterned skirt, are quick snippets of inspiring splendor. Those photobomb moments, coupled with the rock runaway show in the moth dress scene where the protagonist dons a fake Dalmatian coat and skirt outfit, were thought of by Beavan as the antithesis of an average fashion display. Therefore, their revolutionary, energetic, punk essence, the opposite of Baroness’ ordinary and stagnant approach to fashion shows representative of tradition, inspired how the costume designs would look like, be reused, and shift, from leaning towards a more defiant look (motorcycle outfit) to moving into a more militaristic side as satire (British army coat) to going into a more fantastical side (the newspaper/garbage dress).

Kirsten Fletcher, a designer who sculpts fashion into art, was the fashionista Beavan’s team worked with to construct the three photobomb designs and many other costumes. Working at Shepperton Studios in the U.K., where most of Cruella’s garments were weaved and put together, Fletcher had to undertake the challenge of, in Beavan’s words, making “a skirt that you can A) climb onto a car in and, and B) you can swish around to cover up [the car]” in regards to the military/skirt getup. The skirt had to be the perfect weight for it to be light enough for Stone to wear but heavy enough to be swished around the Baroness’ vehicle and stay there. Beavan also mentions that they “did an original version with a more frilly [look], which looked fabulous, but it was too heavy,” so Fletcher and Beavan’s team had to improvise, and after some trial and error, they came up with an idea of layering the skirt with petals. Around 5,060 petals were hand-sewn into the costume by the group, which made it an optimum weight. Fletcher also gave a lot of input into crafting the garbage truck dress, one-of-a-kind, which Beavan states loving making, and Stone mentions as her favorite.

Screenshot Via

I could continue writing about the ludicrous and beautiful garments Cruella wears in the rest of the movie, but the Baroness will be left out of this post for too long if I do so. However, if you would like to know, my favorite outfit is the Cruella DeVil look Stone wears with the half-black (latex?) jacket, half-white (satin?) shirt after (spoiler alert) the Baroness is arrested. It is peculiarly empowering (should I say this?), simple in execution yet succinctly creative with the coat/shirt knitted design, and the perfect balance of white tints and black shades where Cruella’s darker persona overshadows Estella’s brighter side. Moreover, I appreciate that Cruella’s attire when moving into the “Hell Hall” has similar pointed shoulder structures to the ones seen worn by Glen Close’s Cruella de Vil, a subtle reference to a past film and a possible future. So, let us not waste more time and onto Baroness Von Hellman.

The Baroness-The Splendor of the Callous

While Cruella lives in the duality of black and white (splashed with red and grey), the Baroness dwells mostly on browns, golds, and some shades of black. As previously mentioned, she is slightly old-fashioned, having a taste that conforms to the 1950s and ‘60s fashion scene while simultaneously updating them to the ‘70s style, and many times with her, the difference between the concept of a gala dress and a day-to-day garment relies on subtle, yet apparent nuances in color, shape, and texture. She is so fashionable that the clothing she wears to go out often looks as close to Haute-couture as the outfits she wears in her events and galas. The Baroness is the definition of dress to impress. Partnering with costume maker Jane Law, who had previously worked on 1996’s 101 Dalmations and Mad Max: Fury Road with Jenny Beavan, the costume designer took a different approach to creating the prototypes for Emma Thompson’s fitting.

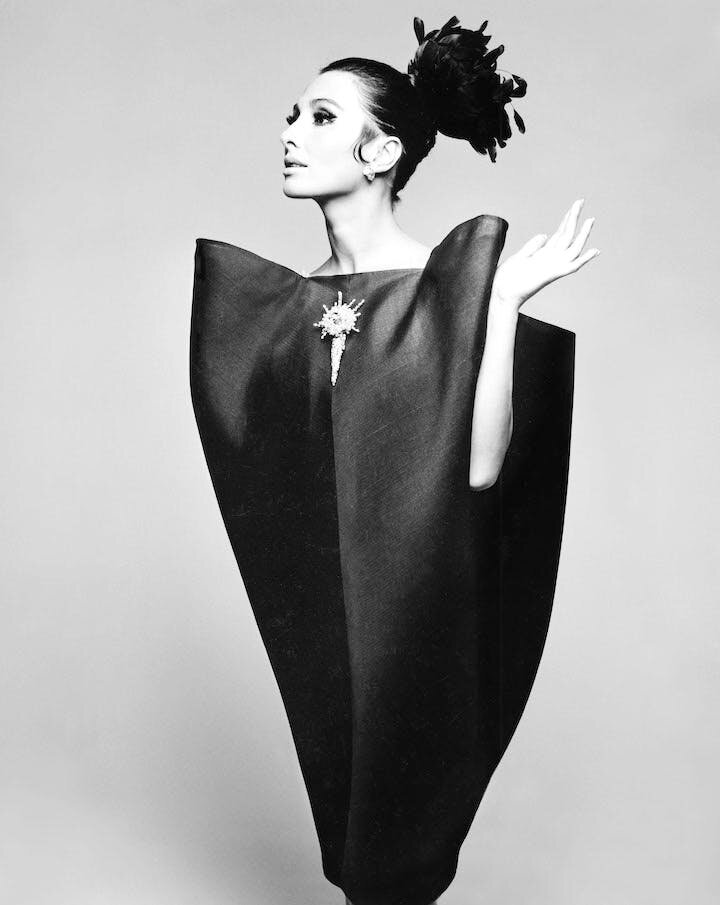

Image Via

Image Via

Because Beavan already knew Thompson from Sense and Sensibility and other previous events, she understood the actress’s shape, framing, style, and general behavior towards wearing the clothes Beavan designed for her. In the Collider interview, she explains that “Emma Thompson has a stunningly good figure and loves wearing clothes like this (...), which also brings something to the whole costume. Some people just stand in it, but she embodies it.” From this previous knowledge, the costume designer bought various fabrics that could work well with both Thompson’s poise and body and the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s fashion aesthetic, giving preference to more sculptural textiles, “fabrics with a good stiffness and body to it.” Then, Beavan and Law would drape the fabrics directly in a mannequin to build the prototype. They would then decide if the prototypes were proper and which scene they would belong in and then call in Thompson to try it all. They aimed to achieve an “obviously asymmetric and very fitted, very snobbish” overall look, as Beavan mentioned in the movie’s virtual press conference.

At the same virtual event, Nadia Stacey, the film’s makeup and hairstylist who did a spectacular job with, in particular, Cruella’s different hairstyles and makeup touch-ups in every single new costume, explained that to conform to the sculpted look of the Baroness, Stacey ran with the idea “that she perfected her look, and everything is kind of variation on a theme.” That is why, throughout the film, the Baroness remains with the same general giant top knot bun hair (sometimes covered with a turban, other times loose, curled, or braided), and her makeup drives focus from her eyelids to her lipstick colors. While Cruella’s makeup and hairstyle constantly change to fit her costumes, where the audience sometimes sees her doing a Harley Quinn and painting her face white or playing with eye shapes and different lipstick colors and glossiness (my true lack of understanding of makeup artistry is showing here), the Baroness’ makeup and hairstyle are modeled to be constant to her personality; fashionable, yet rigid.

Image Via

Finally, at the beginning of Cruella, the Baroness is hosting a ball for her 18th century inspired collection, a highly produced scene that feels more like a “blink and you miss it” moment more than anything. Such a mission to dress a whole room and the movie’s antagonist in highly tailored and fabric-heavy period clothing, especially ones influenced by Marie Antoinette’s outfits, should appear to be a massive undertaking. But it feels like, with today’s enormous interest in period pieces (Bridgerton, The Tudors, Outlander, Elizabeth, Marie Antoinette, The Other Boleyn Girl, Mary Queen of Scotts, The Favorite, Anna Karenina, Pride and Prejudice, anything related to royalty or Jane Austen, really), so many costume houses are specialized in period clothing from almost any century, especially those with the most amount of artistic evidence pointing to their fashion realities. Beavan mentions in the Collider interview that she was quickly able to find the right places that sell the period-accurate textiles and patterns and decided to combine them with “1960’s jewelry, hair, and makeup because people don’t normally do full 18th century [costumes].” Therefore, the costume designer felt it was both possible and doable to recreate the past and blend it with the present’s fashion aesthetic to form an opulent scene that, though brief, was still able to present to the audience that the Baroness was both a creative force and a highly wealthy woman.

Image Via

Fashion is Art

Altogether, Jenny Beavan’s costume designs in Cruella are artfully conceived of, to say the least. Her masterful job in bringing a second life to the 1970s aesthetic in tandem with a more contemporary approach to conceptualization, visual impact, and the crafting process is what the designer excels at in the movie, creating time-appropriate garments that feel timely in Cruella and the Baroness’ bodies. If the movie’s costumes are not given an iconic status in the future — being nominated and receiving several awards, being featured in a fashion exhibition, stirring up some creative trends on the internet based on its looks — I would be shocked and a little disappointed. (Update: Between many accolades, Cruella won Best Costume Design at the 94th Academy Awards and Excellence in Period Film at the 24th Costume Designers Guild Awards). The level of creative input and fashion knowledge applied in coming up with Haute-couture designs that would fit Cruella’s chic and fashionable, yet insanely whimsical rebellious nature was sky high, and adding onto it the Baroness’ luxury label outfits may have set the bar up and opened up new possibilities for future designers to apply their grasp of fashion history, industry, and techniques and combine them with the forever growing creative power of artists in a world where art and design are highly accessible through the internet.

Accordingly, I am not surprised a Cruella sequel got greenlit by Disney. Executives seemed satisfied, audiences flabbergasted by the costumes, and the numbers spoke for themselves (not necessarily the box office ones since the movie is also watchable on Disney + Premier Access). Even though Beavan may not work on this sequel (this is not confirmed, only my own speculation) due to her not been very thrilled with Disney licensing clothing lines from brands like Her Universe and Rag & Bone based on her designs without her direct knowledge nor input of some kind, something that, interestingly enough has happened many times in movies before like Harley Quinn: Birds of Prey, Clueless, and Enchanted, her impact has been felt with vigor. I hope that, if Cruella II actually happens, the costume design is as unique as what Beavan created and that Disney justly treats designers by letting them know beforehand about marketing opportunities and working with them to craft the marketable items. In the same virtual press conference I referenced so many times before, Beavan said, “In fact, in my real life, I have no interest in clothes. I just love telling stories with them. So for me, that was just brilliant,” so I hope she continues telling more stories and inspiring future costume designers to do so. I, for one, am inspired.