Examining The Millennium’s (Cyber)Space Age

While stuck at home, staring at my computer screen from what feels like dawn to dusk, I’ve been thinking a lot about pop culture’s reckonings with technology. Fashion and design often channel the desires and anxieties of the masses into aesthetic innovation, one of the most fascinating examples being the late 1990s-early 2000s space age 2.0: the cyber edition.

This era infused a certain bubbly optimism into a previously self-serious decade dominated by grunge and gangsta rap. The Cold War mentality and fears of a nuclear holocaust were finally fading away, the economy was hopeful, and a bright, utopian, escapist future seemed closer than ever. The late ‘90s embraced a new space age as it saw the possibility for the millennium to either end the world in a crash of binary code or actualize the idyllic future the late 1960s and ‘70s had promised but failed to produce. Unlike the ‘60s space age, this utopia was to be realized not by looking to the stars, but by means of an equally intangible future of extreme connectivity via the Web 2.0. It was believed to promise “a placeless, raceless, bodiless near future enabled by technological progress,” as sociologist Alondra Nelson explains in Future Texts.

This revamped idea of futuristic optimism was reflected in updates on ‘60s space age designs, modernized by the incorporation of “cyber” aesthetics. Advancements like the iMac and Windows 98 became stylistic staples of the era, and bright colors, holographic imagery, and robotics emerged into fashion. There are entire blogs dedicated to the preservation of Y2K-era design in media, architecture, and interior design, but the futuristic niche’s aesthetics and philosophies were best crystalized in music culture.

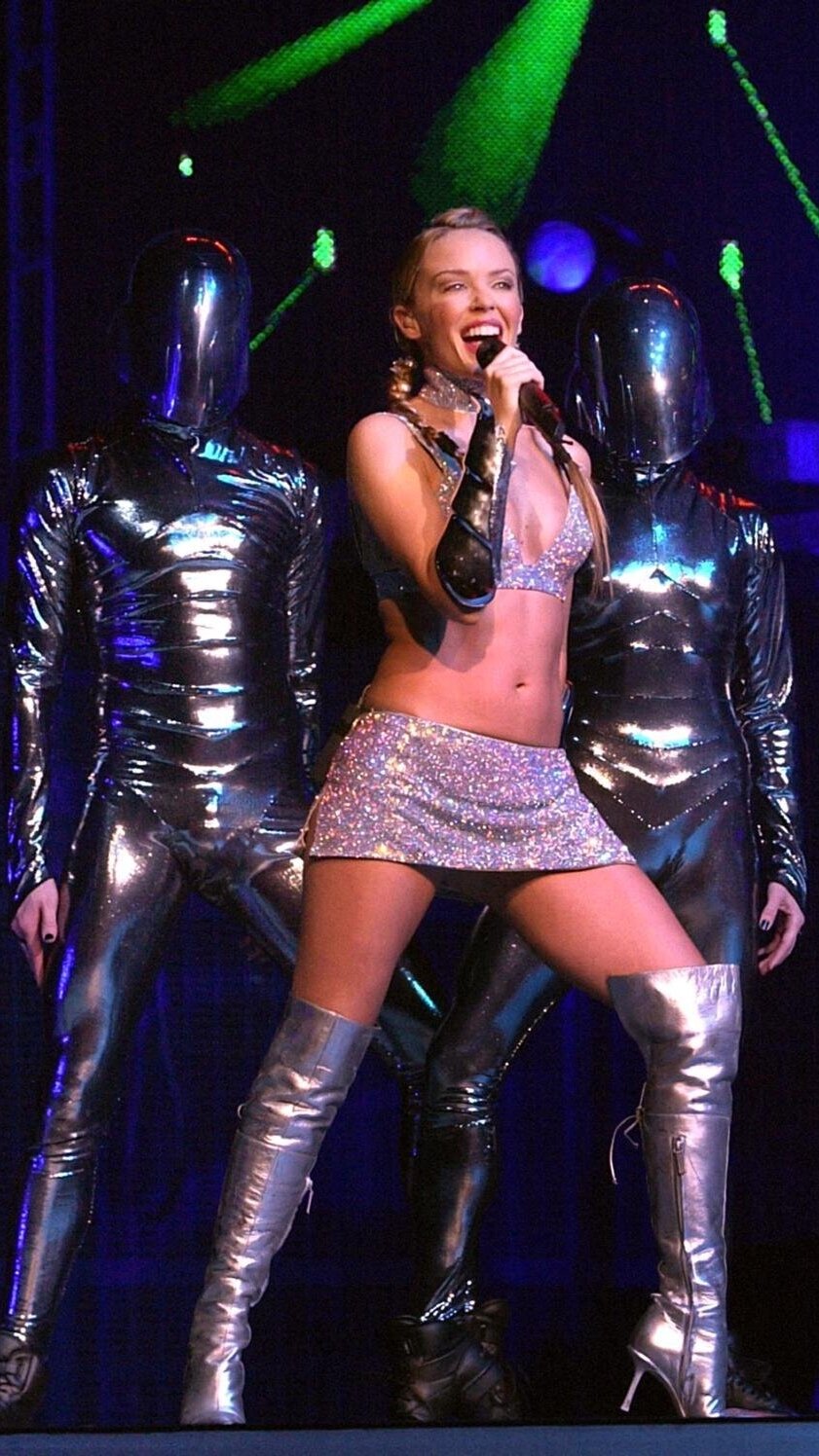

2002: Pop star Kylie Minogue kicked off her concerts by emerging from a “Kyborg” inspired by the female robot Maschinenmensch from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927). Images via here & here.

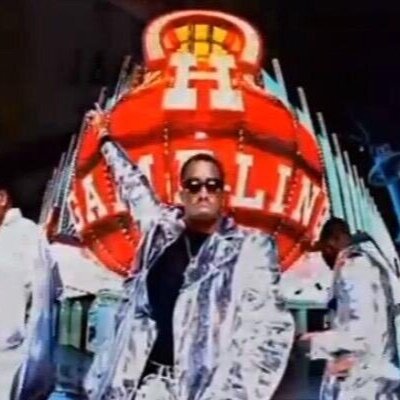

Techno-futurism’s pop culture invasion was pre-empted by the mid-’90s dominations of director Hype Williams’ maximalist, fish-eyed music videos, as his collaborations with the likes of Bad Boy Records and Missy Elliott redefined the visual language of hip-hop. A crucial aspect of Hype Williams videos was their fresh stylistic vision of hip-hop, courtesy of costume designer and frequent Williams collaborator June Ambrose. The first half of the ‘90s was occupied by grittier rap visuals, but Ambrose saw an opportunity to change the mainstream narrative of hip-hop to a lifestyle conflated with glamour and innovation.

Diddy’s Bad Boy Records often celebrated Black capitalism and material gains as a means of liberation, and Ambrose cemented this ethos with her costuming (most famously via Ma$e and Diddy’s infamous “shiny suits”). Ambrose was also behind almost all of Missy Elliott’s timelessly futuristic music video ensembles—including the “Hip Hop Michelin Woman” look in The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly) (1997)—which are still cutting edge 20+ years later.

“[My styling] was about creating these aspirational images that would catapult the culture into a stratosphere in which they were going to economically going to be worthy of. They were making the money and touring the world, so why can’t we be in high fashion? Why can’t we make costumes that are extremely larger than life?” —June Ambrose, via.

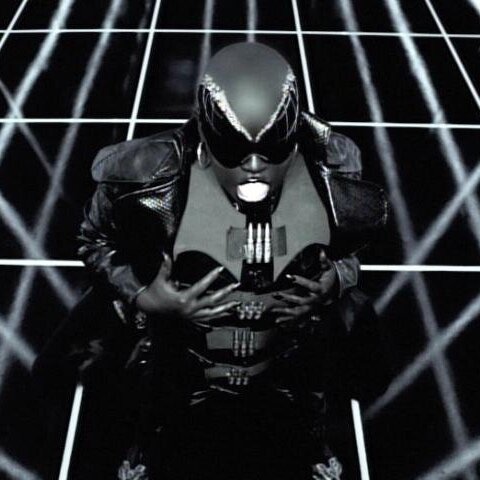

L-R: stills from the music videos for The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly), Mo Money Mo Problems, She’s A Bitch, Feel So Good, and Beep Me 911.

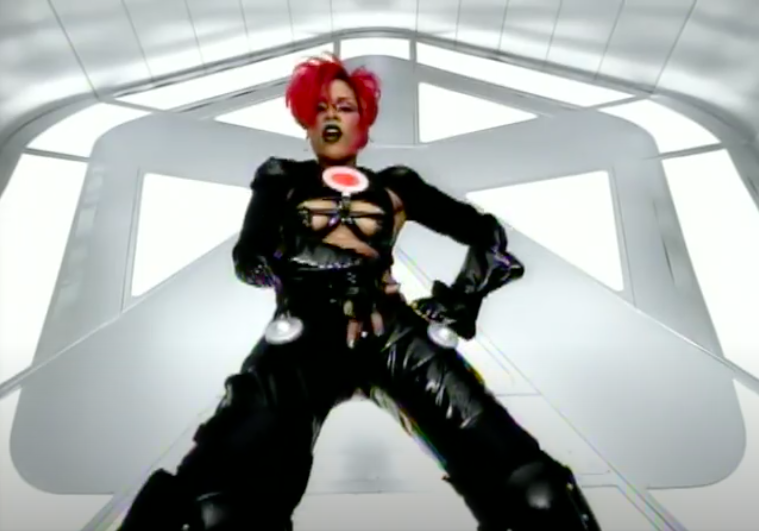

Missy Elliott’s videos can’t be strictly classified under Y2K futurism because they are, quite frankly, in a league of their own. Sock It 2 Me (1997) features Missy, Lil’ Kim, and Da Brat flying high above Earth as robot warriors on a hyper-pigmented alien planet, fighting oppressive androids and dancing through space. She's A Bitch (1999) is a largely monochromatic, militaristic, cyberpunk declaration of unapologetic individualism and power. Missy utilizes the philosophies of Afrofuturism, a multimedia genre which presents “the black cultural experience of freedom achieved through sci-fi, ancient African cosmology and magical realism.”

Visuals from Sock It 2 Me (top) and She’s A Bitch (bottom).

Afrofuturism is a counterpoint to the view that blackness is intrinsically primitive, imagining a world in which space and technology are explicitly tied to Black prosperity. In the ‘70s, the preeminent technological innovation was space travel, and Afrofuturistic art imagined Black people utilizing it to find realms their own. They conceived of being transported, of a mystical mothership to liberate them from the post-Jim Crow physical world which had been laid waste to by racism, poverty, and oppression. In the ‘90s, the idyllic future was a world in which robotics, algorithms, and other budding digital concepts would empower Black people, with the belief that cyberspace could connect the African diaspora across the globe.

One of the most stunning film sequences of all time, from The Wiz (1978). A very Afrofuturistic piece of visual art, mixing distinctly mystical elements with disco, funk, ball culture, ballet, jazz, and modern dance.

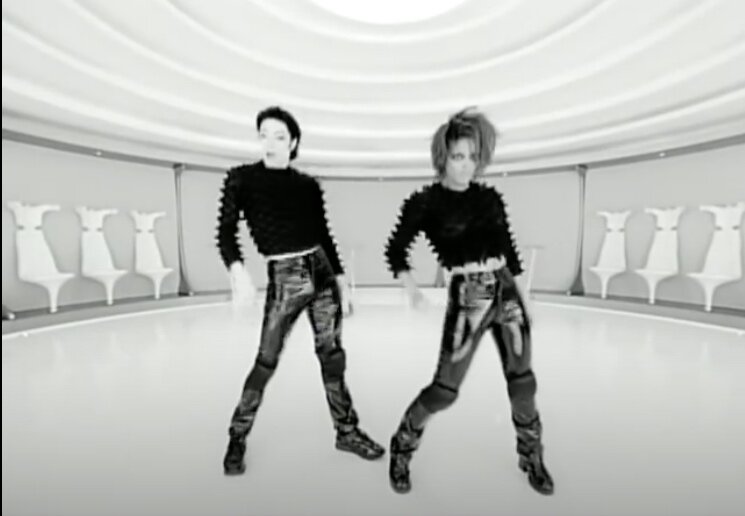

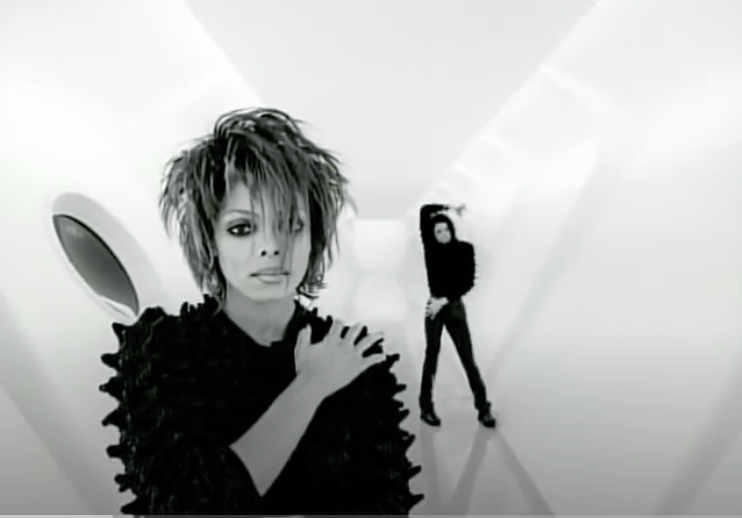

Though Missy x Hype productions proliferated the presence of futurism in pop culture, the video that drew the definitive blueprint for Y2K futurism’s music video design wave was Michael and Janet Jackson’s Scream (1995). The first and only collaboration track between the two, Scream was their musical reckoning with everything that pissed them off about society and the media. Smashing percussion, an industrial soundscape, and tense vocals punctuated their frustrations.

The video followed in Afrofuturistic tradition, imagining space as the only place that the Jacksons could be free from the struggles that plagued their Earhtly lives. The siblings bounce around a hypermodern spaceship complete with a zen garden, squash court, and plenty of furniture and hallway space for them to pose on with maximum angst. Its influence is clear in the set design of the remainder of ‘90s music video interpretations of the future.

As seen in the furniture of Scream, a particularly prominent facet of Y2K futuristic design was the inclusion of callbacks to ‘60s and ‘70s retrofuturism in home design. Fixtures included candy colored interiors, wood paneled walls, plastics, curvy structures, and Verner Panton-esque sets that could’ve come straight out of 2001: A Space Odyssey:

From left to right: images from the music videos for Hands Up, Come On Over, Upside Down, I Do, and Things I Heard Before.

Unlike the extreme sleekness and streamlined design we associate with futurism today, Y2K futurism was optimistic about the integration of the digital with the natural. Blobs, curves, and other biomorphic designs were common. An era-specific manifestation of merging an industrial future with natural elements was the surreal, CGI-liquid effect in music videos:

L-R: images from the music videos for What’s It Gonna Be?!, Carte Blanche, Holla, Baby Come On Over, and Liquid Dreams.

The most common trend in the Y2K futurism school of design was the presence of technological motifs. Though many videos were set in spacecrafts, hangars, or vaguely extraterrestrial-looking tubes, the presence of aliens was essentially replaced by technology. Unlike the ‘60s and ‘70s in which space exploration and extraterrestrial life was the country’s greatest fascination, the late ‘90s and early ‘00s were more occupied with just how advanced and pervasive technology would become. Artificial intelligence, holograms, and futuristic transportation methods were the more pertinent unknowns:

L-R: images from the music videos for Leave It Up To Me, Spice Up Your Life, Bring It All To Me, 15 Minutes, and I’m Gonna Getcha Good.

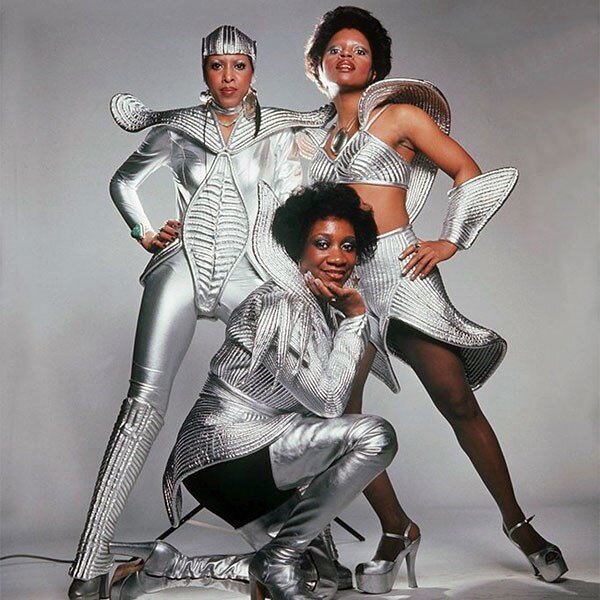

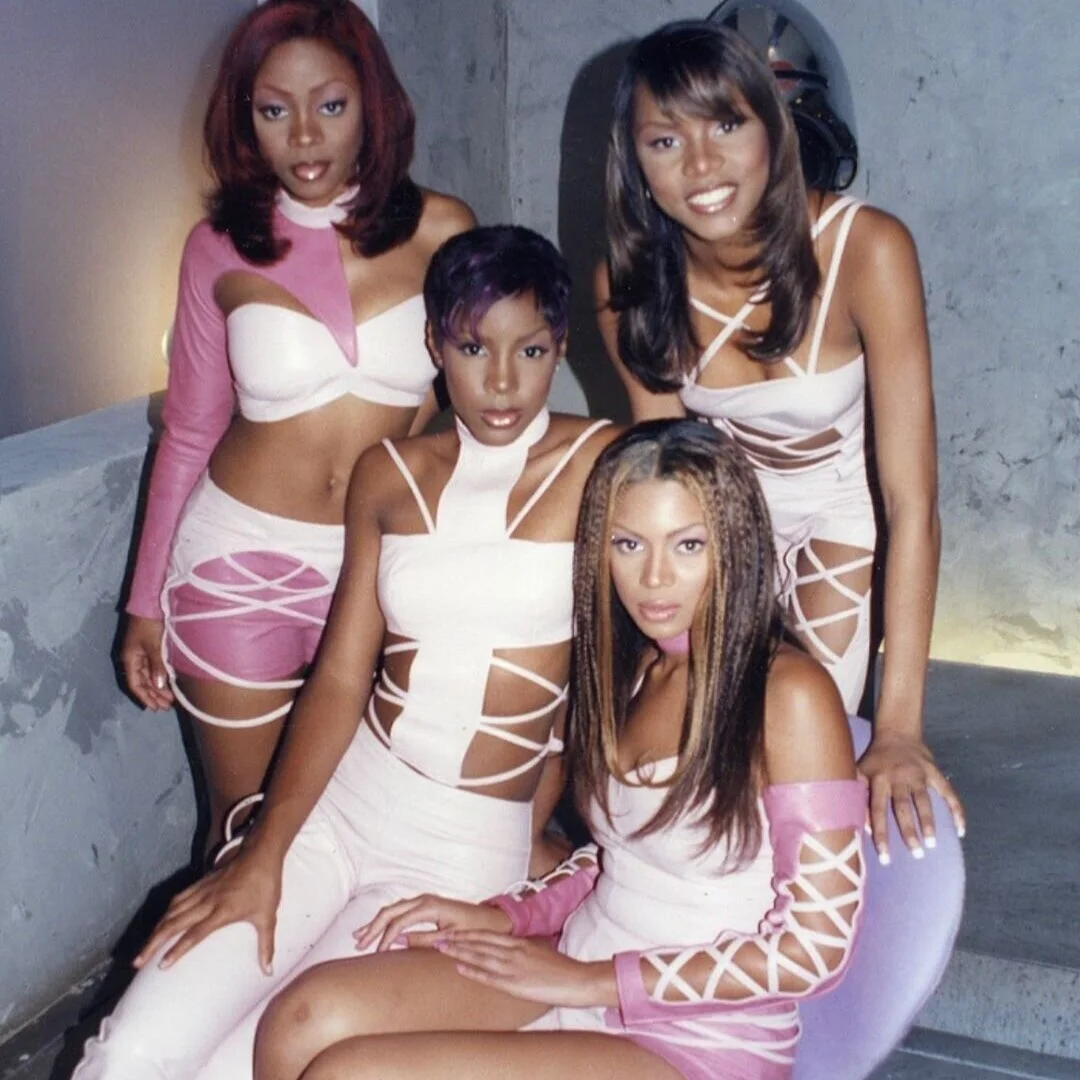

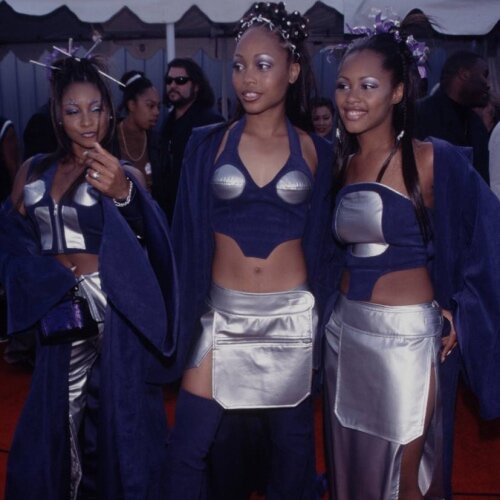

The girl group boom of the late ‘90s leaned particularly hard into futurism, following in the footsteps of ‘70s group Labelle who themselves rode a particularly prominent wave of Afrofuturism. Labelle was originally modeled in the image of a doo-wop, Motown-esque vocal group, but in the ‘70s they pivoted to funk and found massive success. Hits like Lady Marmalade displayed their unflinching power, sexuality, and individuality, and they became the first Black vocal group to be on the cover of Rolling Stone. While more glam rock, sci-fi, extraterrestrial focused designs reflected what the ‘70s thought of as futuristic (see: Parliament Funkadelic, David Bowie), girl groups in the ‘90s pivoted to leather, robotics, and geometric cut-outs.

L-R: Labelle, Destiny’s Child, Blaque, 702, and TLC. Images linked.

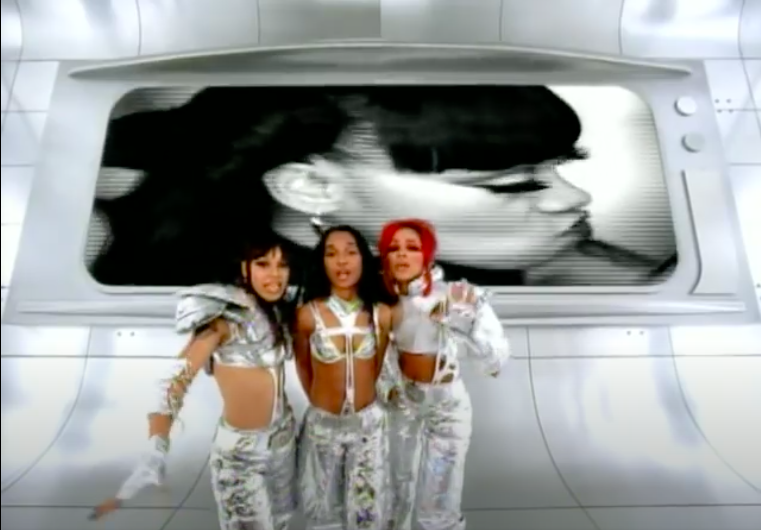

TLC’s entire FanMail (1999) album—released a month before similarly period-defining film The Matrix—was bursting with technological prescience. It was a message to their fans about confidence and the importance of retaining our humanity in the budding digital age (“there's over a thousand ways to communicate in our world today / and it's a shame that we don't connect”). The album cover is coated with binary code and featured the group covered in silver body paint, reminiscent of androids. Their idyllic future was one where archaic gender standards are done away with in favor of independence, sexual liberation, and emotional vulnerability.

The Hype Williams directed video for TLC’s No Scrubs (1999) video was the prototype for the ‘90s girl group plus futurism formula. Heavily influenced by Scream, it was similarly set in a space station in which the artists defy gravity while dancing around various hallways and tubes in black leather and shiny outfits. Alternatively, it included some explicitly late ‘90s aesthetics such as frosty makeup, colorful metallics, and their outfits displayed an overall shift toward the industrial and cyberpunk aesthetics that dominated the remainder of Y2K futurism’s presence in music (see: Blaque’s Bring It All To Me and 702’s You Don’t Know)

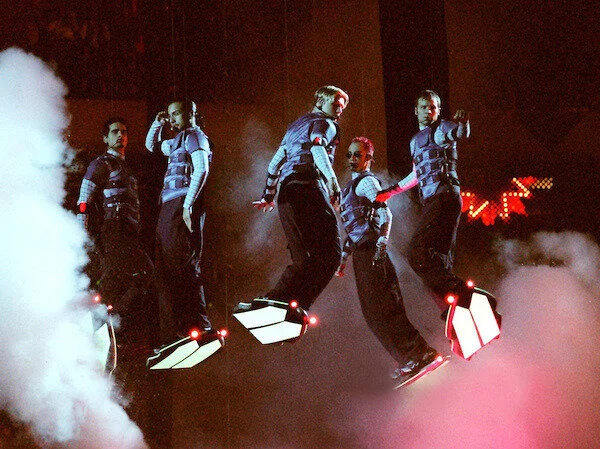

The Y2K futurism aesthetic found its most emphatic teen pop articulation in the music video for the Backstreet Boys’ Larger Than Life, directed by pop culture mainstay Joseph Kahn. It was quite on the nose about its anticipatory Y2K messaging—a single off of the album titled Millennium (1999), the video is located in a spaceship, set in the year 3000. The song itself is a message to their fervent, worldwide fans, expressing gratitude for all their screams and adoration (and allowance money), as they exclaim “all you people can’t you see, can’t you see / how your love’s affecting our reality?” The fans responded in kind, making Larger Than Life the most requested video on MTV’s Total Request Live for a record breaking number of weeks. At this point in their careers, the group was dominating the pop music landscape and the video’s implication was clear: there was nowhere else for them to conquer but the cosmos.

The CGI used was revolutionary at the time, reflected in the $2.1 million price tag. All five Boys star in separate tableaus featuring futuristic tech like androids, cryogenic chambers, and wireless headsets. In the dance breakdown scene, the group sports exceedingly cyberpunk outfits, making for an overall archetypal ‘90s interpretation of the future. They remained thematically consistent throughout the Millennium era, integrating Star Wars music cues, hover boards, and sci-fi inspired armor into their 2000 Into The Millennium tour.

Y2K futuristic design phased out after 2002, following the cultural decline of hope that the new millennium was going to be all that different from the last. 9/11, the Iraq War, the bursting of the dot-com bubble, and the economic crash all seemed to contradict the utopian imagination of Y2K futurism’s aesthetics. In the following years, its showy, bright maximalism would fall from grace—a change made abundantly clear from the new aesthetics of technology, which are often key indicators of how we’re imagining the future. Chunky, rounded, glowy iMacs became sleek, efficient, monochromatic MacBooks.

Lil Nas X, Janelle Monae, Lady Gaga, and FKA Twigs are just a few of the artists that have begun to ride a new wave of pop music futurism. But as phenomena like dubiously ethical CGI, unjust surveillance software, exclusionary social media algorithms, and countless data breaches raise questions about the moral boundaries of our current technological advancements, what could we imagine a techno-utopia to look like in the increasingly dystopian 2020s?

Featured image via, from We Need A Resolution (2001).