Digital Get Down: Music that Anticipated Social Distance

An unanticipated oracle of our times, Soulja Boy has been equipped to make the isolation required of the current public health situation work since 2008. Kiss Me Thru The Phone is a responsible, self-quarantining anthem—he wants to get with his girl but acknowledges that he can’t right now, even though he misses her! He then offers some fantastic alternatives to physical interaction like calling and texting. (America, take notes.)

Music has long been used to chronicle the uncertainties of changing world orders, and in the latter half of the 20th century artists zeroed in on the modern-day industrial revolution: the rapidly changing nature of technology, and its growing presence in our everyday existence.

Aging silent film actress Norma Desmond resents the moviemaking technology that left her behind in Sunset Boulevard (1950). Image via.

One of the first pop hits to retrospectively examine the growth of media technology was British band The Buggles’ Video Killed The Radio Star (1979). It told the familiar tale of cultural obsolescence made possible by an unforeseen advancement in artistic production. After video, the next seismic shift in media saw the “talkies” (film + sound) kill the career of many a silent film star (see: the plots of Singin’ in the Rain and Sunset Boulevard). Actress Clara Bow famously couldn’t stop looking up at the microphones when making her first film with sound, and essentially retired at 25 after suffering a nervous breakdown due to the drastic shift required for her craft. Video Killed The Radio Star was, in a stroke of the most Shakespearian irony, the first music video featured on the innovative new Music Television channel when it launched in 1981. MTV dominated the next few decades, shaping a musical monoculture for two generations of teens until the Internet killed the Music Television star.

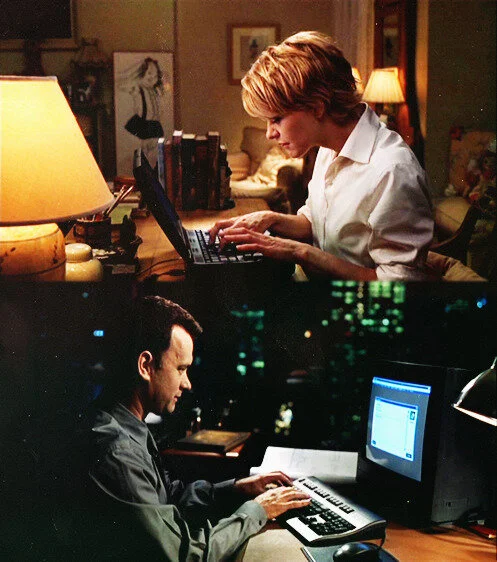

Meg Ryan and Tom Hanks fell in love over AOL in You’ve Got Mail (1998). Image via.

The last few decades have seen music reckon with the omnipresence of technology with varying degrees of excitement. In 1985 (!), Zapp crooned about the vast opportunities to find true love online, claiming “I no longer need astrology / Thanks to modern technology” on Computer Love almost 30 years before the launch of Tinder. Britney Spears transplanted typical post-breakup woes onto the Web with Email My Heart (1999). *NSYNC’s Digital Get Down (2000) was the first song about sexting, with the band more than excited to “get together on the digital screen.” In concert performances, they would burst from a flow of code onto the stage. Lead singer and co-songwriter JC Chasez told Billboard “…it's essentially putting away your inhibitions and sharing something through the digital stream.” There was a pervasive sense of hope that the information highway would simply string the world together, creating an overarching sense of connectivity regardless of physical space.

Alongside this strain of techno-optimism ran artists with a deep-seated fear of the consequences of a drastically altered world. Electric Light Orchestra’s Time (1981) is a concept album that tells the story of a man who travels to 2095, a future plagued with widespread isolation. ELO’s perception of a future governed by alternative modes of communication was one in which softness and connection couldn’t survive. In the analog era, a social life conducted by technology seemed like an emotional death sentence. The third track, Yours Truly, 2095 presents a stark contrast to songs like Computer Love in its view of connection (or lack thereof) in the digital age as the narrator speaks of his 2095 girlfriend:

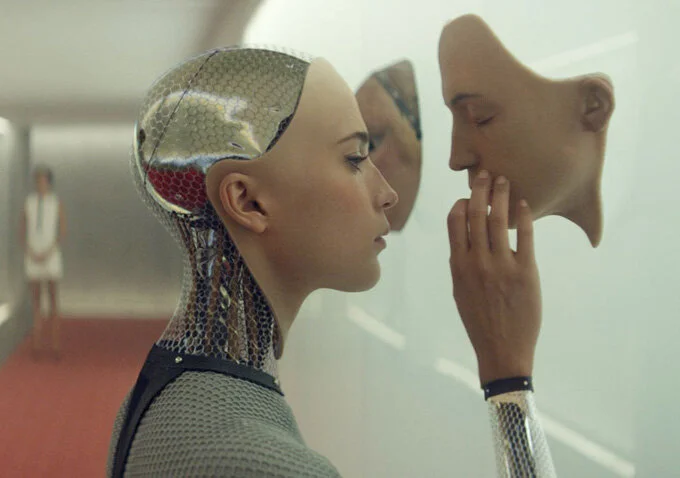

ELO’s futuristic girlfriend sounds an awful lot like Ava from Ex Machina (2014). Image via.

I met someone who looks a lot like you,

She does the things you do, but she is an IBMShe's only programmed to be very nice,

But she's as cold as ice, whenever I get too near,

She tells me that she likes me very much,

But when I try to touch, she makes it all too clear.She is the latest in technology,

Almost mythology, but she has a heart of stone

One decade and zillions of technological advancements later, Prince explored similar themes with My Computer (1996). Firmly ensconced in the MTV era, Prince’s musings on a future governed by the Web were less apocalyptic and more reflective. Ever the pioneer, his philosophy was prescient of the current discourse on technology: machines simply reflect and amplify what we behind the screen are already prone to (à la Black Mirror). In the song he describes a loneliness that isn’t satisfied by any medium—neither paper letters nor phone calls provide a magical fix to social alienation. The Internet is merely another tool with which we can attempt or approximate connection:“I scan my computer looking for a site / Make believe it's a better world, a better life.”

The most comprehensively damning indictment of a digitized future came the next year with Radiohead’s third album OK Computer (1997). Thom Yorke’s signature brand of angst made for a frighteningly recognizable spectre of a socially atomized world. Fitter Happier, a song entirely spoken by early Apple computer voice “Fred” (a sort of proto-Siri), tears into the tension between striving for perfection with what we lose along the way. The song describes seemingly positive goals of modern society in a detached and robotic voice that demonstrates the cold byproducts of said goals:

No longer afraid of the dark or midday shadows, nothing so ridiculously teenage and desperate

Nothing so childish

At a better pace, slower and more calculated

No chance of escape

Now self-employed

Concerned, but powerless

The next few months will surely reveal the possibilities and limitations of online spaces as stay at home orders are extended and our screen time skyrockets. How vast is the capacity for compassion and humanity in online spaces? What do we give up to survive? Which parts of us are translated through the screen and what do we leave behind? We have a pervasive desire to form narratives around history, and living in such a rapidly changing cultural moment makes that frustratingly impossible. I suppose it’ll be up to the artists, bloggers, and academics of the future to see if we become Radiohead-esque Paranoid Androids or if it's possible to live off of Zapp’s proposed Computer Love.

Featured image via