A Look into Graffiti

While admiring art and looking at what we associate with its historical evolution, our thoughts about expressive mediums may range from European Renaissance paintings to the acrylic project you had to turn in for your high school art class. But often times we may forget to go back and explore counterculture artworks that have significant influences and can be spotted in modern creative projects. This mistake of overlooking certain mediums is indeed a common one, so something to remember when we are deciding to interpret a piece, whether that be a fresco or the cheapest canvas you can find at BLICK, is that with art there is a story.

There is a drawing method that falls within the revolution of art history we ironically tend to oversee: graffiti.

This type of art contains historical significance like no other. It can be seen as a political message or as an act of boredom, yet its spread across major cities deserves to be praised.

Personal Experience

As most of you have probably experienced, graffiti can very easily feel like it is only vandalism. It is, in fact, the criminal act of defacing property, and having public infrastructure as a drawing space can make it seem destructive to the original architectural vision intended. Nonetheless, it has earned its title as an ever-evolving medium. Even graffiti artists themselves see the evolution within their lifetime.

I took it upon myself to engage in graffiti throughout Chicago and Miami in hopes to understand the history and meaning of it. One thing I quickly realized in my journey is that it is everywhere because there is no limit to what can be spray painted, but that’s what makes it so accessible and relatable. Cities with a large presence of graffiti artists have transformed a private skill for a niche audience into free art exhibits that are available for millions of people to interact with on a daily basis.

I grew up in Miami, Florida, and although it is a fairly new city compared to Philadelphia or New York City where there is a lot to unload in terms of this artistic style, there is still a concentrated community of street artists in the neighborhood Wynwood. My first time visiting was purely accidental. I realized that my unintentional drive-through-tour of the city was keeping the meter on my car running. With every mile, I continued to get led deeper and deeper into Miami’s graffiti district. While circulating back streets and alleys, I was taken aback by the political messages and colorful murals that lay embedded on every wall and street corner. There was even art on the sidewalk, extending for what seemed like forever. From that moment forward these impressive creations remained cemented in my brain as one of the most unique art forms to interact with. I kept going back to watch the progression of this district filled with artists using small, metal, spray cans to add life and meaning out of thin air.

Today, as I walk around downtown Chicago it is not a rare occurrence to see an array of messages, different fonts, and mind-churning masteries spewed in hidden crevices between buildings. After a few years of being surrounded by street art, I have gathered that this medium must be applauded. Just because the art is rebellious does not make it meaningless. Rather, there is so much passion and many personal stories that have to be unlocked in the visual exploration of graffiti within a city.

History

Graffiti has so much history because it is an umbrella term for any drawing outside of a dedicated space. So, finding the origin of this art form makes it extremely difficult since even cave paintings are considered graffiti. One of the earliest examples goes back 10,000 years, in a cave called La Cueva de las Manos.

This natural landmark in the Argentine Patagonia contains repeated imprints of hands like stencils, in bright hues blending from red, to black, and yellow. There are even scenes of prehistoric life, including stories of hunting and symbols of sacred animals. Looking back this art concept has been around for as long as we have.

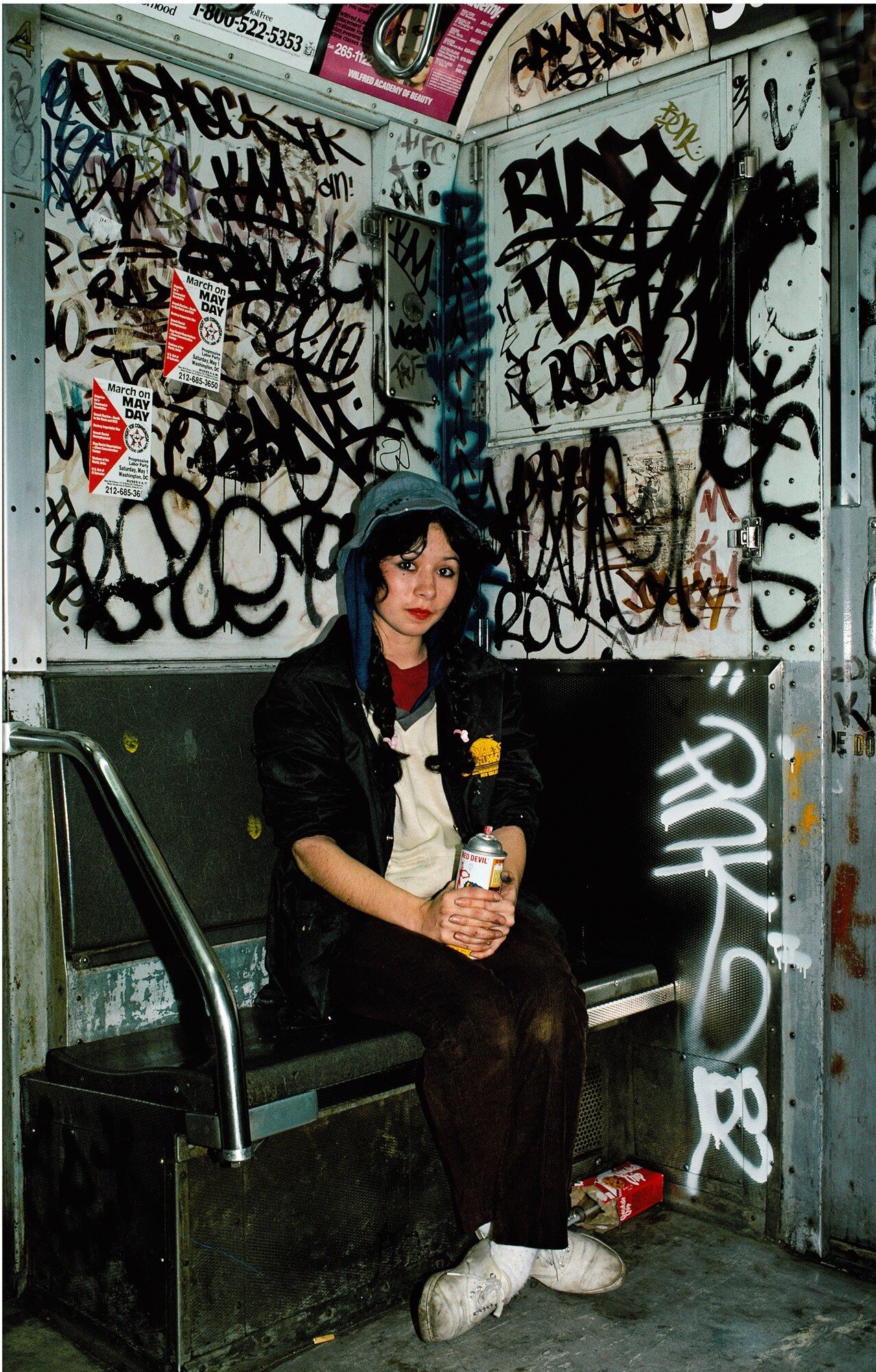

Even though nearly anything can be “street art,” we tend to concentrate on its history within the last six decades when graffiti in urban spaces flourished. This happened in congruence to the rise of spray cans which completely changed the game. A spray can company known as Big Spray became popularized and began surpassing millions of sales of aerosol paint to the U.S. in the 1970s. Its intended purpose was to apply aluminum paint coatings to radiators, but its lightweight, portable, and inexpensive qualities caught the attention of street artists who found them practical for a speedy ejection of compressed color and its permanent application onto surfaces, leaving time to flee the crime scene without a trace.

(Well, except for one).

With a large population in states like Philadelphia and New York, the utilitarian origins of aerosol art became embedded in the visual appearance of the metropolis. The imperfect ensemble of colors by unidentified artists also started tying this idea of rebellion into the process of graffiti. Projecting ideals such as anti-capitalist and counterculture views could be controversial, but what better way to express political opinions than having works displayed across crowded streets and no one knowing who to blame? Even the fact that graffiti itself is imperfect backs its existence as an expressive form of revolt.

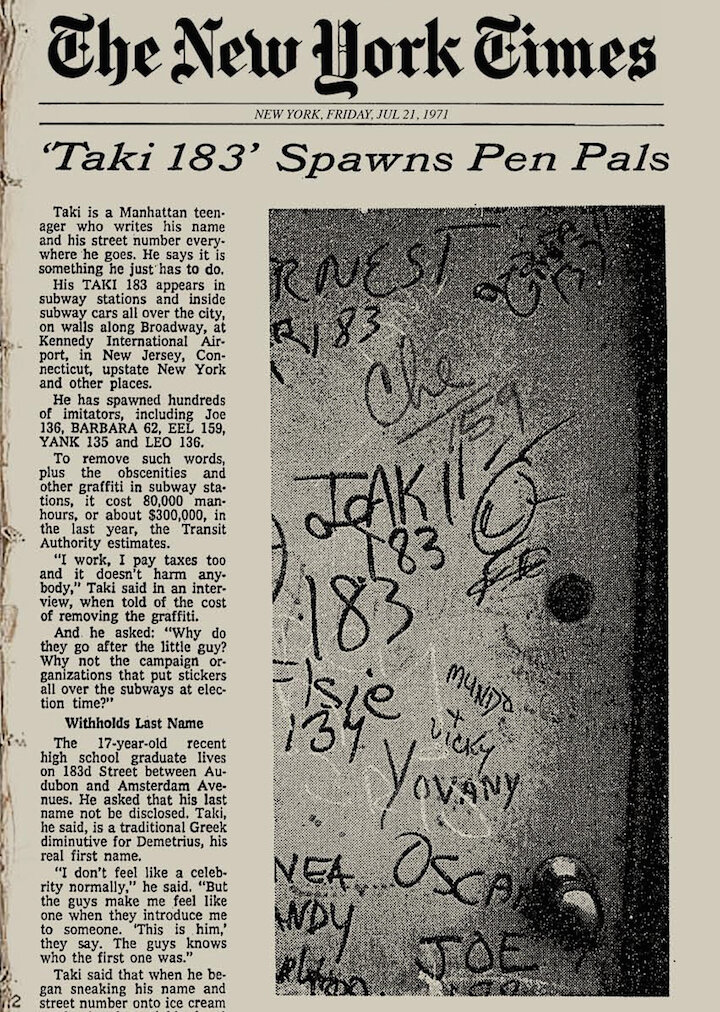

The late 1960s and early 1970s started to see a growth in a form of graffiti called tags: where one writes their name tag (hence, the name) over and over. Tags from local artists started to be noted for their repetitive appearances; some recognized ones were Cornbread from Philadelphia and Julio 204 along with Taki 183 from New York. It’s interesting to break down the meaning of these artists’ tags because they are a lot more innocent than they appear. Taki 183 got inspired by Julio 204, using Taki from his name Demetrius and 183 for the street number where he lived.

Although tags can appear very simple, it is important to understand that just as graffiti itself evolves, the artist during his lifetime does too! It starts with these tags, which soon inspire people to move to bigger pieces. Considering that we are looking at art only a few decades back, it makes sense that the greatest street artists today only developed their craft, and the boundaries of street art, within their lifetime.

As I explored Wynwood Walls for tags I came across the artist by the name of Hec One who gave me a brief recap of his journey into the graffiti world. He told me he began tagging random neighborhood walls in Philadelphia with some friends for fun (as most artists involved in this field do). Then in the ‘80s he moved to Miami and continued to tag: with each growing victory of a mark left behind he would dedicate a little more time to developing interesting looking fonts and prints. From tags to pieces, what was once a hobby started to become his passion. The mix of adrenaline and attention he was gathering was enough to inspire the desire and dedication to continue, and years of adding more visible works led to it becoming his job.

He laughed at the irony. “I got arrested many times in Miami when I was younger for defacing public property, now the city of Miami pays me to create murals on their walls.”

Controversy and Meaning

The controversial aspect of graffiti does not only lie in its vandalism. Its taboo nature is related to the fact that a lot of street art was and is still used to communicate among gangs. Graffiti is a tool that serves to intimidate for territorial dominance. Areas that have been marked by gangs are likely to be under attack, serving as a warning to others not to interfere with activity. After the Los Angeles gang wars in the ’90s, there was an implementation of Graffiti Tracker, an online system that would track gang activities and new additions of graffiti near them. This gang association caused people to rank graffiti as low rather than high art.

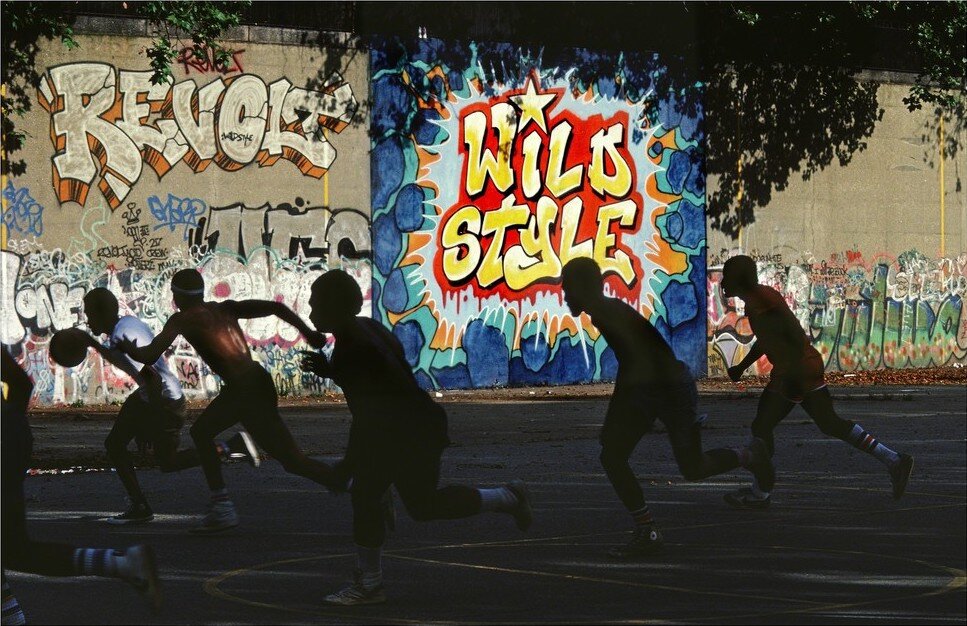

However, because these low-income, gang-infested neighborhoods were mainly underfunded, black neighborhoods, the rise of hip-hop and street art were intertwined. Many emerging hip-hop performers located in New York created tags, “throw ups” or “throwies” (quick artistic tags), and “wildstyles” (very elaborate letterings), of their artist names which simultaneously promoted the art style and their music. Some common names in hip hop graffiti were Fab 5 Freddy and Grandmaster Flowers.

An instance of graffiti in pop is Blondie’s single “Rapture,” where the music video features Jean-Michel Basquiat, a famous graffiti artist from the ’70s that influenced the public to respect the art style. Released in 1980, it was one of the first songs introducing street art into mainstream pop culture that made the medium even more appealing. New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Miami all started to see an influx of those who were passionate about adding color into the busy and dull cities just like the artist I met, Hec One.

Whether it was for aesthetic purposes, to bring light to important political subjects, or for social movement, it was working. Pieces were popping up from day to night and the public began noticing and having conversations that needed to be had.

The best part is that no one could do anything about it: if graffiti was covered it would reappear the next day. It was nightmare for police officers but an inspiration for younger artists that just wanted to be heard.

The strict ban of street art rather than the encouragement to redistribute art and add to the cityscape also makes the illegal aspect of it unattainable for those who have talent but don’t want to challenge authority. The line between what was seen as good or bad was blurry, and slowly it became understood that it just had to be accepted. I mean, look at Wynwood Walls. Rather than having government officials spend the rest of their lives painting over walls, they decided to hire the best artists and promote the district as a tourist attraction. The artists ruled and will continue to do so.

The cultural and artistic nature of graffiti shows that more can be said with images than with words. Social and political themes are very commonly portrayed. For instance, a Wynwood art piece showcases Black culture and empowering messages for young Black folks: in it you see the sight of a jazz player, a woman flexing her muscles, and young smiling Black faces followed by emotions of love and community.

Graffitied messages of gun violence or presidential candidates being mocked the size of a three-story building is an efficient way of voicing an opinion. When the Black Lives Matter movement gained momentum, I saw a significant increase of political pieces by artists who speak with their spray cans. I recently noticed a block-sized mural while walking under the train from Trader Joe’s to my apartment in Hyde Park. These sightings make me appreciate current events and street art more than ever before and I always notice a more accepted view of graffiti by those around me, too.

I am very glad I decided to tackle this article because I have a newfound appreciation for graffiti, the history of it, and what it means today. As someone who is still fully invested in admiring these eighth wonders of the world, all I can say to those reading this article is this.

Make sure you look up and take in the pieces you see around you. It can be a simple tag or the biggest mural you have ever seen; appreciate what it means and its history in order to become the spectator that the artist hoped you would be.

Photographer: Nicole Helou

Model: Laura Sandino